“Nature in the EU is severely declining.” With this simple but incisive statement the European Council introduces its policies on nature restoration, describing the current state of nature in the EU.

With species populations and their habitats under threat, the degradation of nature is posing significant challenges to both people and the planet. Although there have been some limited improvements, recent assessments paint a concerning picture.

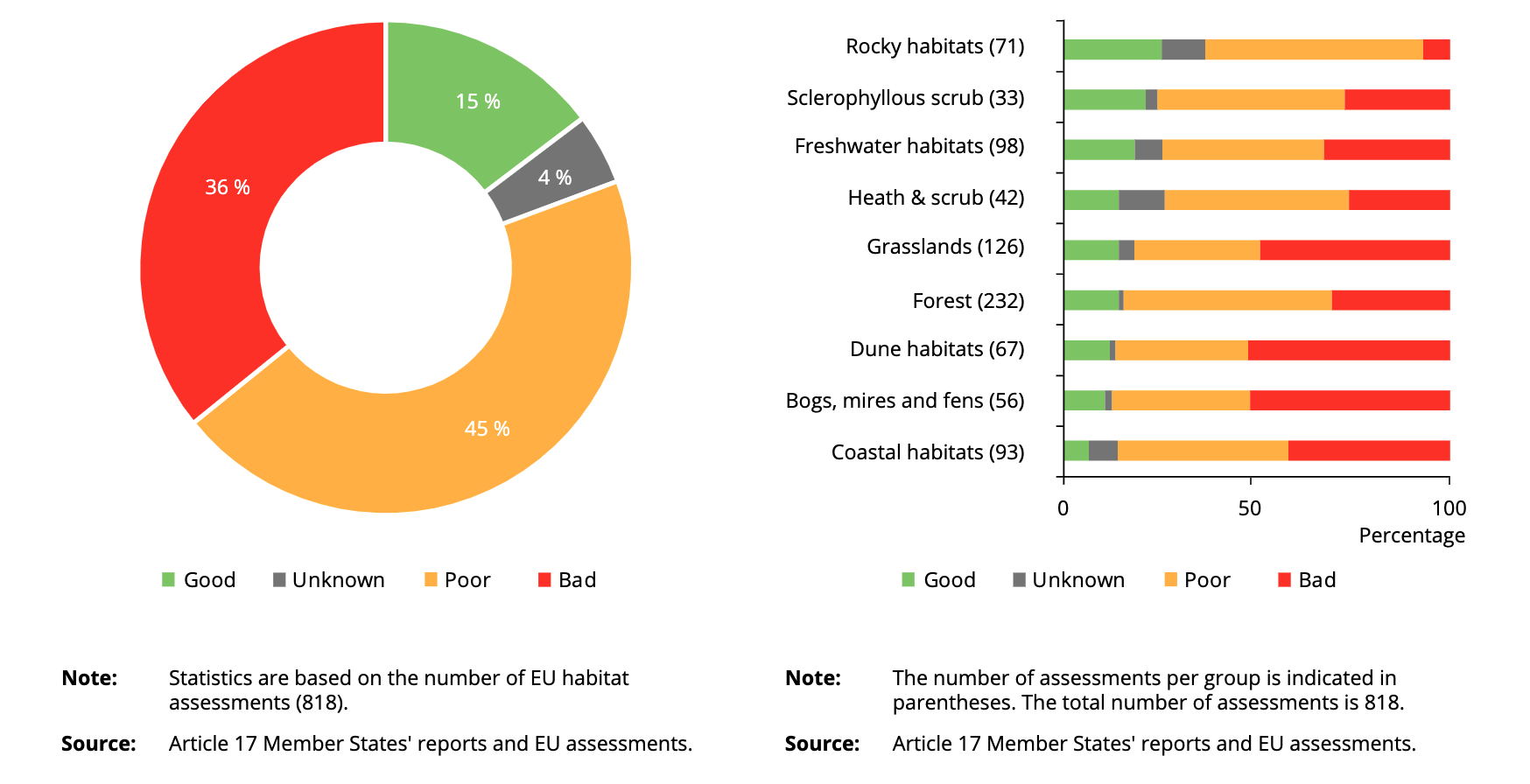

According to a report by the European Environment Agency – “The European environment — state and outlook 2020”, for instance, only 15% of habitats are in good condition, with peatlands and dunes being the most affected.

On the other hand, according to the report, the majority of habitat assessments at the EU regional level show an unfavorable conservation status, with 45% in poor and 36% in bad conditions, totaling more than 80%.

Moreover, over one third of EU habitats and species in poor or bad state are further deteriorating, with only 9% of habitats and 6% of species showing improvement.

Nature is essential for food production, as highlighted by the Council, with almost €5 billion of the EU’s annual agricultural output attributed to insect pollinators. However, about 50% of areas where pollinator-dependent crops are grown do not provide suitable conditions for pollinators like bees and butterflies. As a result, these vital pollinators are in a very poor condition in the EU, with one in three species in decline and one in ten on the brink of extinction.

Various factors contribute to this pressure on ecosystems and species populations, including pollution, climate change, habitat loss, and invasive species. Despite long-standing efforts to preserve nature and biodiversity through laws like the Birds Directive adopted in 1979, nature in the EUcontinues to decline.

In response, the EU is making efforts to develop a new law that helps restore nature and species. The Nature Restoration Law aims to establish binding targets for key ecosystems, habitats, and the species within them, reversing current trends and ensuring a healthier environment for both wildlife and people.

What is the EU’s Nature Restoration Law?

The Nature Restoration Law “is seen by the European Commission as a key part of meeting the EU’s climate and biodiversity goals. It aims to restore at least 20% of the EU’s land and sea areas by 2030,” as reported by Carbon Brief.

Proposed by the European Commission in 2022, the law is considered a fundamental step towards nature restoration, addressing the adverse impacts on wildlife, human health, food security, and water supply resulting from nature degradation.

As stated by the European Commission, the “proposal for a Nature Restoration Law is the first continent-wide, comprehensive law of its kind. It is a key element of the EU Biodiversity Strategy, which calls for binding targets to restore degraded ecosystems, in particular those with the most potential to capture and store carbon and to prevent and reduce the impact of natural disasters.”

Originally conceived to fulfill various objectives outlined by the Commission, the law aimed to restore a range of ecosystems, including “wetlands, rivers, forests, grasslands, marine ecosystems, and the species they host” as a means to enhance biodiversity throughout Europe.

Moreover, the law sought to safeguard essential ecosystem services such as water and air purification, crop pollination, and flood prevention, ensuring the preservation of these services provided by nature, that is, to “secure the things nature does for free”.

Notably, the European Commission stresses that every euro invested in nature restoration is projected to yield substantial benefits ranging from 4 EUR to 38 EUR.

Additionally, the law aimed to contribute to the global effort to limit warming to 1.5°C, thereby assisting in climate change mitigation. It also aimed to enhance Europe’s resilience and strategic autonomy by strengthening its ecosystems, mitigating natural disasters, and reducing risks to food security.

As highlighted by Politico, “healthy ecosystems are also a vital component of fighting climate change: Over-exploited forests can turn from carbon vacuums into emissions hubs, while planting trees and quenching dry marshlands help absorb planet-warming pollution.”

The original proposal from the European Commission included the objective of restoring 20% of the EU’s land and sea areas by 2030 and all areas in need of repair by 2050. Additionally, it outlined sub-targets for specific habitat types such as wetlands, forests, rivers, and oceans, as well as for pollinators, cities, and agriculture.

The proposed law sets ambitious objectives aimed at restoring ecosystems, habitats, and species across the European Union’s vast land and sea territories. At its core, the proposal seeks to facilitate the “long-term and sustained recovery of diverse and resilient nature” within the EU, where 81% of habitats are currently in poor condition.

The proposal addressed diverse ecosystems such as urban and agricultural areas, with the goal of achieving “no net loss of green urban space by 2030 and increasing green urban areas by 2040 and 2050.”

In agricultural landscapes, targets focus on enhancing biodiversity and carbon sequestration while restoring drained peatlands. Marine ecosystem restoration efforts target vital habitats like seagrass beds and sediment bottoms, crucial for climate change mitigation, along with the habitats of emblematic marine species.

Moreover, the proposal prioritizes river connectivity, aiming to identify and remove barriers hindering the flow of surface waters. By 2030, the objective was set to restore at least 25,000 kilometers of rivers to a free-flowing state, fostering healthier aquatic ecosystems and bolstering biodiversity conservation efforts.

Nature Restoration Law – a political rollercoaster

Following the original proposal from the European Commission in 2022, the Nature Restoration Law has faced criticism, backlash and diplomatic challenges, resulting in significant revisions. The result is a law that the aforementioned Politico article describes as “emptied out and watered down”.

The revised law no longer includes requirements for restoring agricultural land, and targets for reviving drained peatland are now voluntary for farmers and private landowners. Despite retaining headline targets for 2030 and 2050, key provisions related to agricultural land restoration and specific urban greening targets have been removed after a year of negotiations.

According to Politico, the law now exempts governments from legally binding targets to restore areas beyond those already protected under the Natura 2000 network until 2030. Furthermore, binding targets have been weakened, and a mechanism to suspend rules during food security crises has been introduced.

Revisions to the Nature Restoration Law, initially a crucial component of the European Green Deal, were prompted by farmer protests and right-wing populist sentiments among EU lawmakers. Furthermore, dissatisfaction persists among several countries, including Sweden, Finland, Poland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Hungary. Their objections, primarily driven by concerns over regulatory overreach, disproportionate costs, and ideological differences, now pose a threat to the law’s adoption.

The vote at #ENV @EU_Council on Nature Restoration Law was regrettably not sealed today as it should have.

Yet I am optimistic & I believe the Member States can bring it over the finish line.

It’s the only way forward to meet our international & climate targets. pic.twitter.com/6E5wWchFuR

— Virginijus Sinkevičius (@VSinkevicius) March 25, 2024

The bill’s journey through the European Parliament was tumultuous, marked by controversy as conservative lawmakers, notably the European People’s Party (EPP), succeeded in watering down its provisions before ultimately voting against it.

As a result, the law faces potential rejection in its final stage. The tight timeline before the EU elections further complicates the legislation’s fate, as any modifications would require parliamentary approval, making adoption before the current Parliament’s term ends in late April unlikely.

Originally scheduled for finalization during an EU environment ministers’ meeting, the vote was unexpectedly removed from the agenda due to a lack of necessary support.

“It can’t really be the law itself,” said German Green politician Steffi Lemke, as quoted by Politico. “Too many changes have been made in the negotiations and far too many points have been included,” and despite being significantly weakened, the Nature Restoration Law has become symbolic of the electoral battle surrounding the future of the Green Deal.

This anticipated setback underscores Europe’s waning enthusiasm for green regulations, particularly in agriculture, despite the enactment of numerous climate legislations in recent years.

Read more: