The UN Climate Action Summit, one of a series of climate-related events that drew attention to climate change this month – including the largest global climate mobilizations ever – culminating on September 23 with the world leaders’ commitments for climate action. What happened at the UN Headquarters in New York and why it wasn’t a climate meeting like the others.

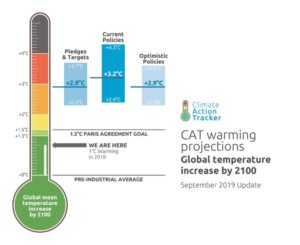

With the Paris Agreement (2015), countries pledged to keep global temperature rise this century “well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius”. Nevertheless, actual commitments under the Paris Agreement set by countries are insufficient to reach the goal, as they are more in line with a “+ 3 degrees” future.

Countries have also agreed to re-submit their climate plans (Nationally Determined Contributions – NDCs) by 2020 for the first time, in order to close the gap between actual commitments and those compatible with the Paris goal. Prior to the 2020 deadline, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres called on all leaders to go to the Climate Action Summit in New York with concrete, realistic plans to enhance their NDCs by 2020, in line with reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 45% over the next decade, and to net zero emissions by 2050. Guterres’s requests were coherent with the 1.5 °C goal, the more restrictive global warming level that – in the meantime – has been further explored by the IPCC in the Global Warming of 1.5 ºC report.

Homework done?

The assignment was clear. We want to keep global temperature rise at 1,5 degrees; to reach this goal, we’ll have to reach carbon neutrality (globally) by 2050. The question to be answered is: how would you (your country) contribute to meeting this goal?

“Bring plans, not speeches,” Guterres recommended, while suggesting some actions: “First, let’s shift taxes from salaries to carbon. Second, stop subsidizing fossil fuels. Third, stop building new coal plants by 2020.” Only 63 countries were given a three-minute platform to speak at the Summit, as those without “ambitious targets” were not let onto the stage.

Unsurprisingly, the question remains unanswered by most countries: even with no disagreements on the 1,5 °C premise, not many countries are committed to zero emissions by 2050 and the Summit has seen a lack of commitment from the biggest emitters.

China, the largest GHG emitter, confirmed that they will meet the pledge they made under the Paris Agreement – that unfortunately is not in line with the 1,5, nor with the 2-degree target – without announcing an increased ambition as of yet. No news from the US, as they were not one of the countries speaking: Donald Trump entered the Summit but stayed only briefly. The pledge of the third world emitter is, at least, compatible with the 2-degree target, but India promised a boost in its use of renewable power without referring to strengthening its target and without reference to a coal phase out.

“We can win this race”, says @antonioguterres

as #ClimateActionSummit ends. “Summit was a boost, but we are not there yet, have a long way to go. Need more action from more countries and businesses. Repeat my appeal to nations: no new #coal beyond 2020!”https://t.co/BtAi1sFJqV pic.twitter.com/TLL7wyGbj9— The UN Climate Action Summit (@UNClimateSummit) September 24, 2019

The generations to come

Waiting for more ambitious pledges to arrive by the formal 2020 deadline, the Summit has been the occasion with which to speed up the process, to raise awareness, to capture the media’s attention. And young people’s involvement has been central in building momentum. Apart from the massive youth mobilizations that animated New York City and the entire world, UN Secretary-General convened the first summit for young people completely devoted to climate action. On September 21, the Youth Climate Summit officially opened the three day event at the UN Headquarters with a full day program for young leaders who are driving climate action.

Moreover, the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg was invited to give a speech on September 23 just after Guterres’ opening remarks. Among the various declarations at the Summit, Greta’s speech [click here to read the full transcription] has been without doubt the most quoted and discussed by mainstream media. “How dare you?”, repeated the 16 year old girl, accusing leaders of not doing enough for effective climate action. After the speech, Greta and 15 other children filed a complaint against five of the world’s leading economies for having violated the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child by not taking adequate action against climate change. The five named countries were Germany, France, Brazil, Argentina and Turkey, the largest emitters that have ratified the convention, but “This isn’t about just 5 nations” the signatories specified.

Today at 11:30 I and 15 other children from around the world filed a legal complaint against 5 nations over the climate crisis through the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

These 5 nations are the largest emitters that have ratified the convention.https://t.co/ZSyDMTYFSF— Greta Thunberg (@GretaThunberg) September 23, 2019

There is good news indeed

Let’s start with Finland, that moved up its carbon-neutral goal from 2035 to 2033 and committed to be “carbon negative” soon afterwards.

Russia (unlike Turkey) announced the ratification of the Paris Agreement. Very good news if we think that the fourth global emitter of greenhouse gases in now on board. Nevertheless, this doesn’t help much, as Russia’s NDC is – for now – so weak that it would not require a decrease in GHG emissions from current levels, according to Climate Action Tracker.

Germany committed to carbon neutrality by 2050; France announced that it would not enter into any trade agreement with countries that have policies which counter the Paris Agreement and – together with other countries – that will not allow oil or gas exploration on their lands or off-shore waters.

“Smaller countries, including Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries, were among those who made the biggest pledges, despite the fact the they have contributed the least to the problem” the official UN press release states. The number of countries and cities committed to net zero carbon emissions by 2050 reached respectively 65 and over 100 at the Summit. Several countries announced that they will work to phase out coal, and 70 would boost their Paris pledges by 2020.

Private sector action was encouraging, with 87 major companies with a combined market capitalization of over USD 2.3 trillion pledged to reduce emissions and align their businesses with a 1.5°C future. Since the first 28 companies committed to 1.5°C were announced in July, the number has more than tripled. 130 banks – one-third of the global banking sector – signed up to align their businesses with the Paris agreement goals.

Climate Finance also stepped forward. Among the major results highlighted by the UN, 12 countries made financial commitments to the Green Climate Fund, the official financial mechanism to assist developing countries in adaptation and mitigation practices. The new pledges have raised the replenishment from USD5.2 to beyond USD 7.4 billion (but the goal is to mobilize USD100 billion per year by 2020). Furthermore, the Climate Investment Platform was officially announced at the Summit. It will seek to directly mobilize USD 1 trillion in clean energy investment by 2025 in 20 Less Developed Countries in its first year.

What happens next

This is quite clear. As Guterres said at the end of the Summit, “we are not there yet, we have a long way to go”. According to Climate Action Tracker’s projections released just before the Summit, without more action, warming could reach 1.5˚C by 2035, 2˚C by 2053, 3.2˚C by 2100. As the Summit did not represent a turning point, it will be worth keeping progress monitored between now and the end of 2020, when governments are requested to submit much more ambitious Paris Agreement commitments.