The hot summer months are upon us and, with roughly two billion units in operation around the world, air conditioning is increasingly the go-to refuge from the blistering heat. But, what happens when turning on the AC is either too expensive or simply not an option?

Cooling poverty refers to the financial burden of cooling on lower-income households, particularly in developing countries. The term includes both the inability to afford adequate cooling technology and the regressive nature of the costs incurred, whereby a disproportionate share of household budgets are set aside for the electricity needed for cooling by lower-income households.

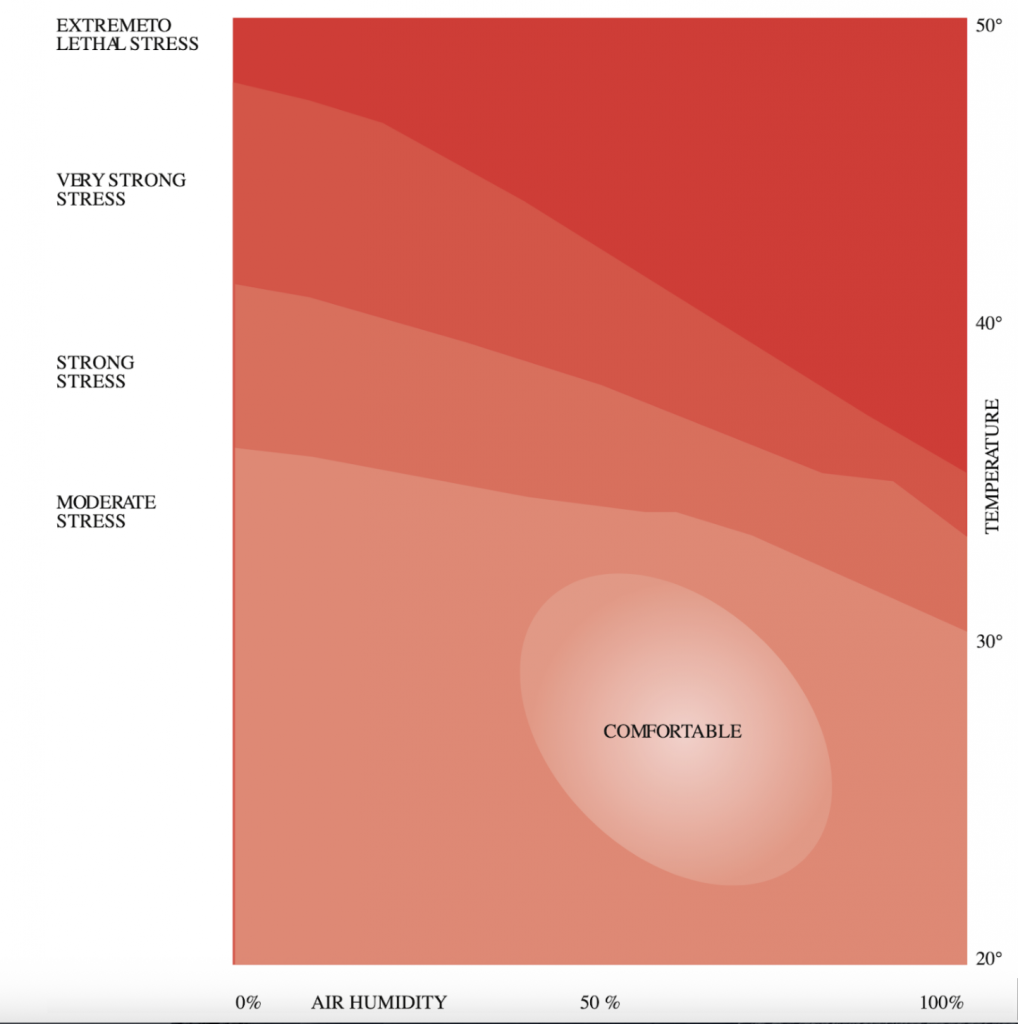

Standing on the shoulders of established definitions of energy poverty – which traditionally focused on heating needs, cooling poverty extends its scope to address the emerging challenge of staying cool in an increasingly hot world. A necessity that extends beyond acquiring and powering air conditioners to encompass systemic factors that expose organisations, households and individuals to the detrimental effects of increasing heat stress.

First outlined by CMCC researcher Antonella Mazzone, systemic cooling poverty encompasses the state of available cooling provision for outdoor working, education, health, and refrigeration purposes. In this sense, cooling poverty goes beyond reflections on energy and its costs, embracing a multidimensional, multi-leveled analysis of infrastructures, spaces, and bodies. Tackling the issue is therefore not just about ensuring access to air conditioners, running much deeper.

CMCC researcher Enrica De Cian, co-author of a study that defines systemic cooling poverty, emphasises how “the concept has many important policy implications, as it points at the importance of addressing the risks related to heat exposure with effective coordination between different sectors, such as housing, healthcare, food and agriculture, transport.”

Just how unequal is access to cooling

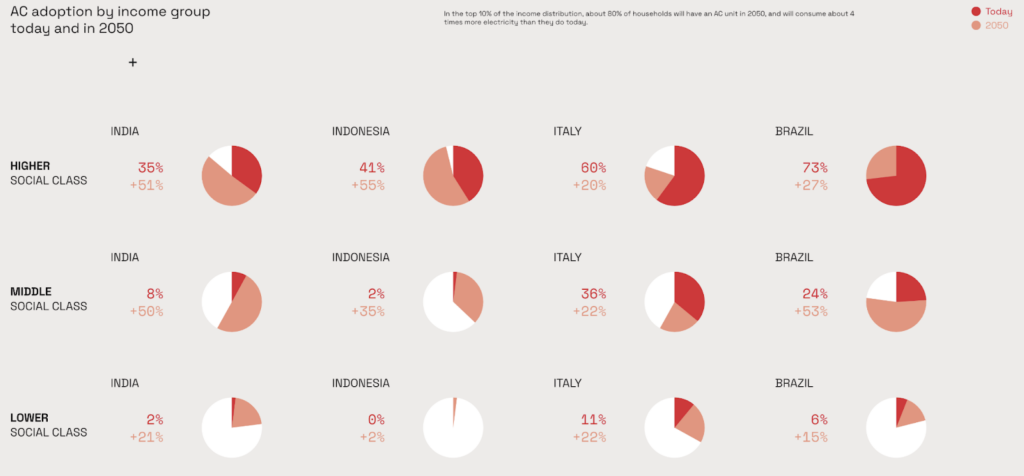

A large part of cooling poverty revolves around the issue of unequal access, with studies revealing alarming disparities in air conditioning use and affordability both now and in the future.

In a first of its kind assessment of how air conditioning impacts electricity consumption, CMCC researchers De Cian, Giacomo Falchetta and Filippo Pavanello, analyze 25 countries representing 62% of the world’s population. Published in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, the study reveals how air conditioning ownership increases household electricity consumption by 36% on average globally.

A trend that is not equal across nations. In fact, the marginal effects of air conditioning ownership on electricity consumption by country offer a further clue as to how cooling impacts nations both differently and unequally, with air conditioning increasing average electricity consumption by about 68% in Africa, 10% in Italy, and 7% in non-European OECD countries.

When putting the increase in energy use into a financial perspective a crucial detail that highlights the disparities endemic in cooling poverty emerges: whereas high-income households allocate just 0.2% to 2.5% of their expenditure on air conditioning, expenditure in some of the poorest households can reach up to 8% of their budget on electricity for cooling. A vicious cycle that sees poorer households face the greatest financial burden.

“In developing countries, a substantial fraction of households that adopt air conditioning will be low income, and will face significant expenditure burdens to attain thermal comfort, raising the spectre of cooling poverty,” explains Falchetta.

A growing crisis: Projections for 2050

The implications of these findings become even more concerning when viewed through the lens of future climate projections. The research shows that air conditioning prevalence will grow from the current global average of 28% to 41-55% by 2050. However, this growth will be highly unequal across regions. For example, African countries are projected to see penetration rates of only 9-15%, well below the global average.

What is more, the increase in use of air conditioning will also have an impact on global emissions, resulting in a negative feedback loop. By 2050, global residential electricity demand for cooling could reach nearly 1,400 TWh annually – comparable to India’s total electricity consumption in 2020 – resulting in additional 670-956 million tons of CO2 emissions – comparable to the entire annual greenhouse gas emissions of Germany – and associated costs of $124-177 billion.

A global trend that is clearly playing out on a local scale. Just by way of example, in Italy air conditioning installation increases average household electricity consumption by 36%, creating disproportionate hardship for vulnerable households that are forced to choose between staying cool and meeting other basic needs.

Cooling solutions that go beyond technology

The “Cooling Solution” exhibition, currently showcased at Institut français Milano through July 22, 2025, uses a combination of science, photography and interactive installations to investigate how people of different socioeconomic backgrounds adapt to high temperatures and humidity across Brazil, India, Indonesia, and Italy.

The exhibition, featuring photography by Gaia Squarci and research by the ENERGYA team coordinated by De Cian, challenges the paradigm that air conditioning is the only solution to rising temperatures. It offers a visual journey through people’s lived experiences of ineffective and inefficient cooling, hypercooling, heat dumping, vernacular architecture, and cutting-edge cooling technologies.

The emergence of cooling poverty represents a stark example of how climate change impacts fall disproportionately on the world’s most vulnerable populations. An issue that is particularly relevant as global temperatures continue to rise, widening the cooling gap. Thermal adaptation and adequate cooling need to be seen as more than just a luxury for the wealthy; they are a necessity which requires equitable and sustainable solutions.