Green roofs, urban gardens, public parks, “water places”, river contracts, and much more: there are many examples of the Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) that are starting to re-design and change appearances and relationships within our cities.

The European Commission defines nature-based solutions to societal challenges as “solutions that are inspired and supported by nature, which are cost-effective, simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic benefits and help build resilience. Such solutions bring more and more diverse, nature and natural features and processes into cities, landscapes and seascapes, through locally adapted, resource-efficient and systemic interventions.”

So, what exactly does innovating with nature mean? What goals can be achieved by fully exploiting the potential of Nature-Based Solutions? We discussed the topic with Margaretha Breil, CMCC researcher at ECIP Division, where she focuses on climate change adaptation and urban resilience.

“In urban planning NBS are already a standard”, she explains. “Before applying any types of engineering solutions, practitioners and developers are now trying to use natural solutions or approaches able to imitate natural features and processes. This is because NBS present a series of advantages that traditional grey solutions don’t have. Green infrastructure in urban areas often appear as the best way to achieve environmental targets, promote social development and improve social welfare. Public parks, gardens and urban forests, are in fact created for multiple purposes and offer a variety of valuable ecosystem services, such as water flow regulation and run off mitigation, flood control and prevention, regulation of air quality by urban trees and forests, urban temperature regulation, nature-based recreation etc.; a grey or engineering solution, e.g. a dam to collect water, can fulfil just one function at a time, while a NBS always serves more than one function.”

The most advanced and cutting edge examples of NBS come from the northern hemisphere.

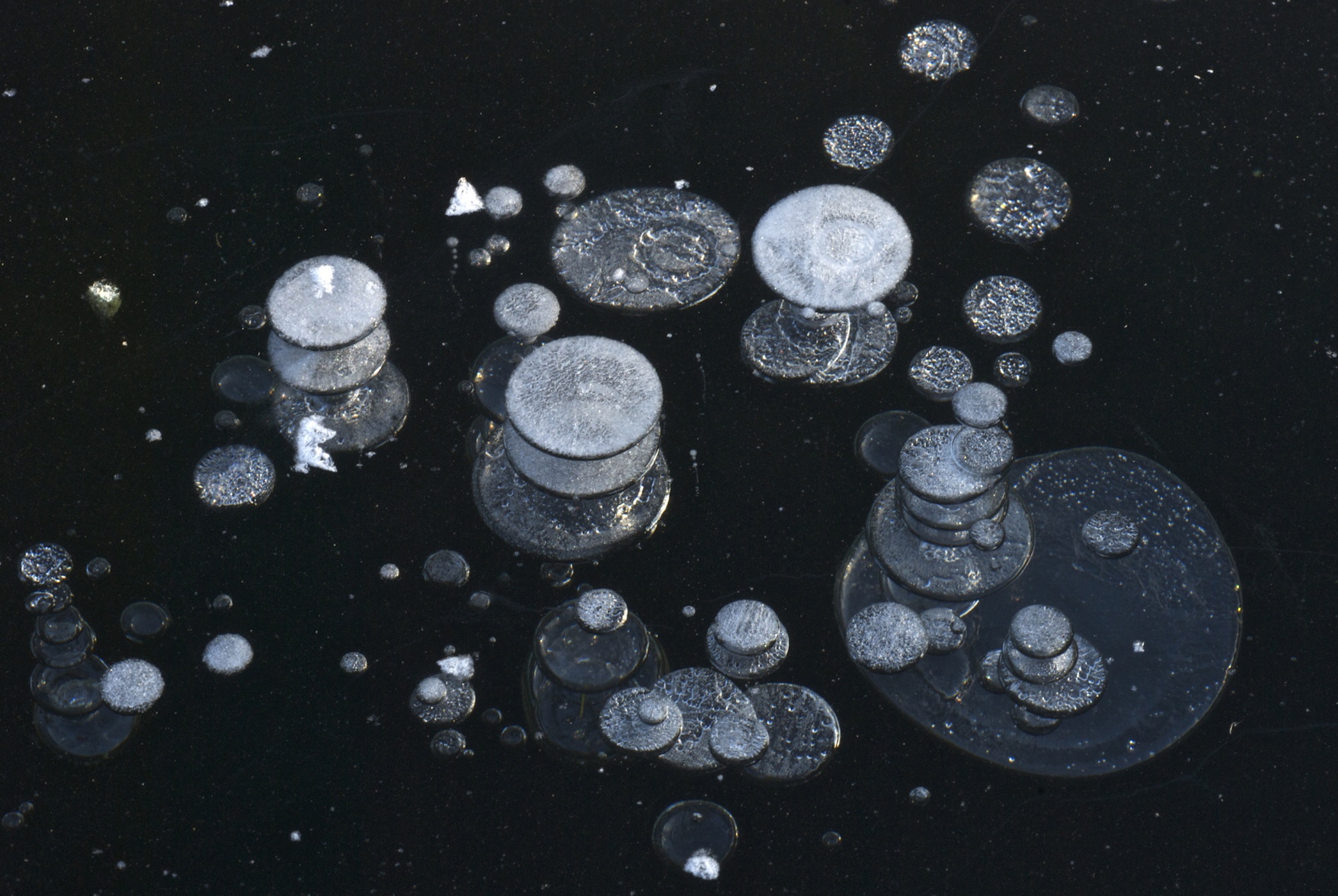

In July 2011, in less than two hours, Copenhagen was hit by an extreme storm event where 150 mm of rain left large areas of the city under up to one meter of water. The 2011 event had been preceded by high-intensity rain in August 2010 and was followed by another one in 2014.

So, the city established the Cloudburst Management Plan which outlines the methods, priorities, and measures recommended for the area of climate adaptation including extreme rainfall. The Copenhagen Formula adapts interdisciplinary approaches and combines conventional infrastructures with Blue-Green solutions; the expected benefits (in approximately 20 years) are many: a flood peak reduction, increase infiltration / water storage, reduce load to sewer system, health, environmental, and urban spatial quality improvements, etc. “Moreover, a detailed cost-effective analysis realized by the city”, Dr. Breil explains, “showed that the option with the highest percentage of Blue-Green solutions and also the least additional infrastructural pipe improvements created potential savings of 50% more than engineering solutions alone.”

The Copenhagen case study highlights that “blue-green” is the future for establishing urban ecological waterscapes while balancing sound investment and economic opportunities with social benefit improvements.

Examples of urban regeneration through green solutions are many: the NBS implemented through the Carta of Milan, the city’s strategic environmental plan; “Vertical forest” in Milan and the “Forest House – 25 Verde” in Turin; the green corridors of Barcelona; the peculiar case study of Augustenborg neighbourhood (Malmö, Sweden), an example of public initiative and building that solves the problem of flooding while improving the image of the area, with the creation of sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS), including 6km of water channels and ten retention ponds, etc.

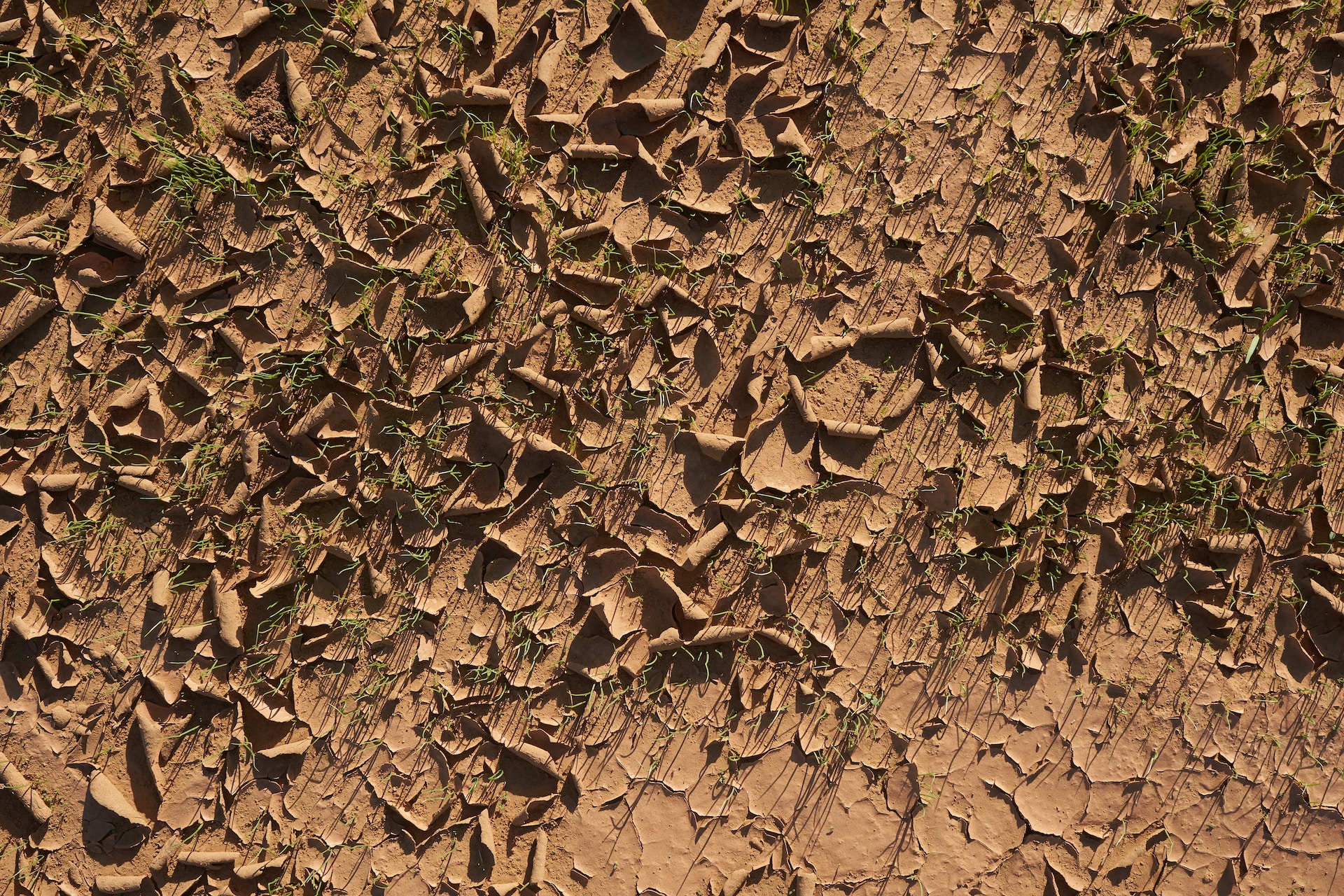

What are major hindrances to the spread of Nature-Based Solutions around the world? The need for interdisciplinary knowledge and collaboration among different institutions and local authorities is a major obstacle to the spread of NBS. Moreover, another impediment to the spread of NBS everywhere is that not every green infrastructure is universally applicable. “Research and knowledge developed in the North, may not be fully useful in the South”, Margaretha Breil explains. “So, we need to develop a knowledge base that is better adapted to Mediterranean and developing countries’ characteristics, that is more nuanced to regional differences and needs.”

Who should enjoy the benefits of ecosystem services? Do people have equal access to those benefits? If we believe in NBS to urban challenges, from sustainability to liveability, then we should also believe in the fair and equitable access to such solutions. In some ways all green infrastructure designs and implementations imply decisions about justice and equity.

David Maddox, founder and Editor in Chief of The Nature of Cities, an international platform to share diverse, transformative ideas about cities as ecosystems of people, nature, and infrastructure, is sure about the fact that access to “green” is an issue of justice.

“Classically”, he explains, “the environmental justice movement has focused on the geographic distribution of environmental risks while highlighting that generally speaking poor communities disproportionately suffer the burden of pollution from the systems that sustain affluent lifestyles elsewhere. If we believe that green is a value, and that trees, parks, open spaces all have dramatic benefits for liveability, health and happiness, we should fight to guarantee access to these services for everyone. We should ask the question: do we truly believe in the benefits of ecosystem services, and who deserves them? The answer should be obvious: everyone. However, does everyone enjoy these benefits? In short: no. This issue hasn’t been solved yet: poorer neighbourhoods around the world tend to have less access to parks and other green elements, nor does everyone have equal access to NBS that can provide resilience to heavy precipitation events, floods, storms, heat waves and other extreme events exacerbated by climate change.”

Even when green infrastructures are included in the design of neighbourhoods, there can be unintended results. First, planners often impose green elements without consulting community members about their will and needs. Such a lack of inclusive, participatory decision-making can produce green spaces that are ill-suited for the neighbourhood.

Another unexpected, negative result of NBS is “gentrification”. As nature based solutions are put in place, neighbourhoods may become more desirable to people living in other places; their value may increase, rents and housing values may rise, and many residents can no longer afford to live there and are forced to move, priced out of their improved neighbourhoods.

“To avoid people displacement”, David Maddox argues, “the ‘green’ must be not only a technical or science issue: we all have to become activists about the questions of environmental justice for change towards better cities. We need to understand that green should be part of the ‘must haves’ of cities, such as housing and transportation, because it is strongly connected with the quality of our lives.”

Another key issue is transparency: “we need open, public data”, David Maddox adds, “we can’t have an open conversation about NBS and smart cities without it. A lack of transparency and open knowledge can cause poor decision-making or even corruption. The situation is particularly critical in developing countries where a persistent lack of investments and government instability can result in a lack of publicly open data.”

Finally, we must conceive and build our urban spaces based on a vision of the future that creates cities that are resilient, sustainable, liveable and just. And this implies difficult choices, with winners and losers. How to avoid these problems? Being specific about the choices related to resilience, or sustainability, or liveability or justice, and the trade-offs they imply.

As suggested by the most interesting examples of NBS and plans, it’s important to set specific targets we can work on. “The US NGO The Trust for Public Land for example launched the #10minuteswalk campaign, suggesting that everyone deserves a park within a 10-minute walk of home. The beauty of an idea like this, simple, easy to communicate but with a lot of science behind”, Maddox explains, “can become an issue for politics and create specific goals for cities in terms of planning. We have to take action in social, legal and political contexts to move nature-based solutions forwards. In particular, we need formal actions at the level of politics justified and rationalized by science. This issue is wider than cities: governments, institutions, civil society, education, the media and the people, all need to act and be engaged.”

For further information:

- The Nature-based solutions webpage of the European Commission.

- The Nature of Cities website

- The report “Nature-based solutions to promote climate resilience in urban areas – developing an impact evaluation framework” prepared by the EKLIPSE Expert Working Group on Nature-based Solutions to Promote Climate Resilience in Urban Areas (among the experts, the CMCC Foundation researcher Margaretha Breil). The report has been requested by the European Commission DG Research and Innovation to assess the benefits and challenges of applying NBS.

-

Nature-Based Solutions case studies.

1. The Cloudburst Management Plan of the city of Copenhagen

2. Milan, NBS for urban regeneration

4. The “House Forest – 25 VERDE” in Turin

4. Barcelona

5. Urban storm water management in Augustenborg, Malmö and some images of green infrastructure