The World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting has come to a close after four days of intense talks, bringing together the world’s foremost political, business, cultural and other leaders to decide on global, regional and industry agendas.

In this year’s May edition, the first summer edition in the history of the event, leaders could not escape the global context of war in Ukraine, rising global inflation, food shortages in developing countries and an unfolding energy crisis.

However, climate issues still managed to make their way to the foreground throughout proceedings in Switzerland, with some leaders stressing the need to interweave the unfolding global crises and find solutions that tackle them in unison, whereas others advocated for putting climate issues to a side – at least temporarily.

With observers speculating on the waning power of the “Davos Man” – attendance was down less than half compared to the previous edition, not least of which due to the absence of Russia and a reduced Chinese delegation due to Covid restrictions – and critics questioning the Davos elite’s commitment to climate over profit, let’s take a look at some of the main talking points and in particular how the climate issue was addressed.

The climate in the foreground

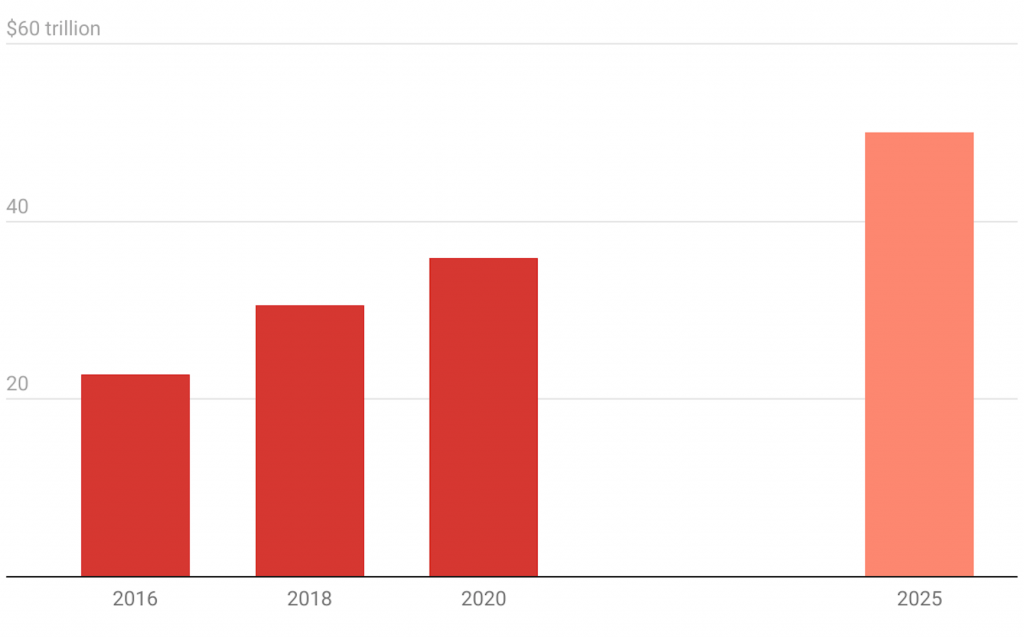

One topic that featured most heavily, is that of the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) agenda, with the WEF calling for the adoption of universal and common standards and disclosures to establish the corner stones on ESG, with over 150 companies now signed up to the framework for Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics, plus 70 having adopted it, to date.

The importance of ESG in shaping the way the private sector is set to address climate issues cannot be understated. There are currently 2.7 trillion USD in assets now managed in more than 2,900 ESG funds leading the Financial Times reporter Gillian Tett to describe auditors and accountants as suddenly “wildly trendy”.

However, the ESG topic was shrouded in controversy when HSBC’s head of responsible investing, Stuart Kirk, declared that policymakers are exaggerating the financial risks of climate change claiming that it is simply “not a financial risk that we need to worry about.”

Although his comments received strong backlash, leading to his suspension, there remain many skeptics, including Tesla’s founder and billionaire Elon Musk who recently labeled ESG as a “scam”, frowing petrol on the flames of the already heated debate on the merits and demerits of ESG.

Moving on from ESG, the WEF also declared its partnership with the US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and over 50 global businesses to invest in innovative green technologies, with over twenty new companies and eight countries joining the First Movers Coalition, which aims to decarbonize the heavy industry and long-distance transport sectors responsible for 30% of global emissions, signaling a significant expansion from when it was formed last year at COP26.

The companies include Microsoft and Ford Motor, which announced that they will turn to “green” steel, aluminum and other commodities by 2030. The coalition’s market cap amounts to approximately 8.5 trillion USD across five continents, and committing to advance purchase commitments by 2030 aimed at helping clean tech grow.

Rich Lesser, global chair of Boston Consulting Group described this as “an incredibly important demand signal” to help unleash the trillions of dollars of investment needed for the climate transition, when speaking to the Financial Times.

A transition that will undoubtedly require international cooperation. John Kerry, America’s top official on climate change, told the Associated Press that China and the US, the world’s largest emitters of greenhouse gasses, were close to agreeing on the structure of the group and releasing a new progress report.

Excited to announce that the First Movers Coalition is expanding. #WEF22

✅ 55 companies (more than 10% of Fortune Global 2000 market value).

✅ 9 government partners representing nearly half of global GDP.

✅ 6 sectors and $10 billion of purchasing pledges.— Special Presidential Envoy John Kerry (@ClimateEnvoy) May 25, 2022

And China didnt just stop there, declaring that they plan to plant and conserve 70 billion trees in one of the most ambitious country pledges announced at the WEF. A move that was however welcomed with cautious optimism. Tom Crowther, an environmental scientist at ETH Zurich explains that: “Promoting nature at large scales can be fantastic if done in an ecologically responsible way, but it should not distract from efforts to decarbonize,” when talking to Time Magazine.

Finally the issue of carbon markets was also on the tip of leader’s tongues. According ot the Financial Times the market is under heavy scrutiny from critics who fear that the carbon impact of many offset projects is being exaggerated, and that companies may be able to take advantage of low-quality carbon credits to claim “net zero” status while continuing to heat the planet. Concerns have been raised, too, about how strong a role the corporate and financial sector plays in the standard-setting initiative.

In contrast, Standard Chartered chief executive Bill Winters told a Davos audience that lack of action on voluntary carbon markets from the private and non-governmental sectors would be detrimental to the fight against climate change. “Governments may or may not set the standards objectively. They’ve got political considerations,” whereas the private sector would “set the standards, and they’ll be very high.”

Overall the consensus in Davos is that there is a need for a price on Carbon. Jim Hagemann Snabe, the chairman of Siemens, told The New York Times that the “most sharp knife in the arsenal of policymakers” when it comes to fighting climate change is putting a global price on CO2 emissions.

Davos, therefore, offers a peek into what the private and public sector consider to be their top priorities to both tackle climate cahnge and continue to profit. However, leaders were also forced to contend with the elephant in the room: war in Europe and the ripening economic, energy and food crises.

Interwoven crises

Speaking at the Energy Outlook: Overcoming the Crisis panel on Monday, Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency outlined how: “We are in the middle of the first global energy crisis. In the Seventies, it was the oil crisis and now we have an oil crisis, a natural gas crisis, a coal crisis – all prices are skyrocketing and energy security is a priority for many governments, if not all.”

At the same panel Dmytro Kuleba, Ukraine’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, warned that a multi-year food crisis is looming if the conflict with Russia continues to thwart Ukraine’s ability to export food supplies. Countries like Egypt and Tunisia, that rely heavily on food imports, may struggle to meet demand and around 20 countries have currently put restrictions on food and fertilizer exports due to shortages and rising prices.

David Beasley, executive director of the United Nations World Food Programme, declaring that: “We were facing an extraordinary food crisis before Ukraine, food costs, commodity prices, shipping costs were already doubling, tripling, quadrupling,” and that the number of people “marching to starvation” has risen from 80 million to 276 million over the last four to five years.

If ports in the #Odesa region do not open up immediately, two things will happen:

First, we're going to have agricultural collapse across #Ukraine. Second, famines will be looming all over the world. Food needs to move, ports must reopen and this needs to happen NOW. pic.twitter.com/G3xIFShBjJ

— David Beasley (@WFPChief) May 6, 2022

However, Birol was also careful to connect the energy crisis to climate issues, commenting that, “We don’t need to choose between an energy crisis and a climate crisis – we can solve both of them with the right investment.”

A point of view shared by Catherine MacGregor, CEO of French utility giant Engie, who focused on how: “the energy transition can be a solution to that energy independence challenge that is thrown at us.”

Robert Haback, Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, was also quick to point out that the economic crisis, energy crisis, food poverty and climate crisis are interwoven and must be addressed together.

“But if none of the problems are solved, I am really worried we are running into a global recession, with a tremendous effect on climate action but also on global stability. Imagine that part of the world is starving next year, it’s not only about hunger, which is terrible enough, it’s about global stability,” he explained to the WEF panel.

However, representatives from emerging economies were not so convinced, with The Economist reporting that “one Western boss after another got an earful from their emerging-market counterparts about the global knock-on effects of the American-led sanctions against Russia on food and fuel prices.”

In fact, Hardeep Singh Puri, Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas, highlighted how the current energy crisis, and in particular the skyrocketing price of oil and the highest inflation rates in 50 years, are global issues and that focusing on climate change should not hinder our ability to tackle it. “We need to be able to successfully navigate out of the current crisis without adding more problems in terms of sustainability and going green.”

A view that is also held by Amin Nasser, the chief executive of Saudi Aramco, who told the Financial Times: “[The world is] not taking seriously the issue of energy security, affordability and availability.”

A matter of priorities

Conflicting views on the interwoven nature of the ongoing crises and how to tackle them reveals how different regional interests dictated agendas at the WEF. According to Karim Raslan, in his opinion piece for the South China Morning Post, “How can it be a “World” Economic Forum when the concerns of Asia, which will contribute 60 per cent of global growth by 2030, are disregarded?”

Davos shows Southeast Asia must increasingly look out for its own interests https://t.co/3ptcJr7Fd5

— South China Morning Post (@SCMPNews) May 29, 2022

However, some experts, such as Johan Rockstrom, a director of the Potsdam Institute on Climate Impact Research, told Bloomberg that “this time high-level politicians and the biggest economies in the world are really trying to keep two balls in the air at the same time.”

Not all are convinced. Adam Tooze, professor of history at Columbia University, told Bloomberg reporters that addressing climate change at Davos has become the easiest global problem to solve for these leaders. “It’s a long-term issue and the time horizon over which a conference like this makes sense” and that the solutions being proposed by leaders “are not radical,” and simply “a place of win-win promises.”

Jeremy Raguain, a fellow at the Association of Small Island States, also highlighted how corporate interests hold a large amount of power over climate-related policies of governments in large economies. “The science is clear, but there are many well-funded lobbyists. Who’s in the room when the science is being fought over to make policy?” he said during his address.