Energy development is deeply connected to a wide range of socio-economic issues. Nowhere is this more evident than in Africa where the deployment of renewable energy is increasingly seen as a game changer, whereby sustainable, clean energy can become a catalyst for far ranging social and economic development.

The irony is that although Africa is home to 17% of the world’s population it only accounts for 4% global energy demand, with approximately 43% of the continent’s population, roughly 600 million people, currently lacking access to reliable electricity.

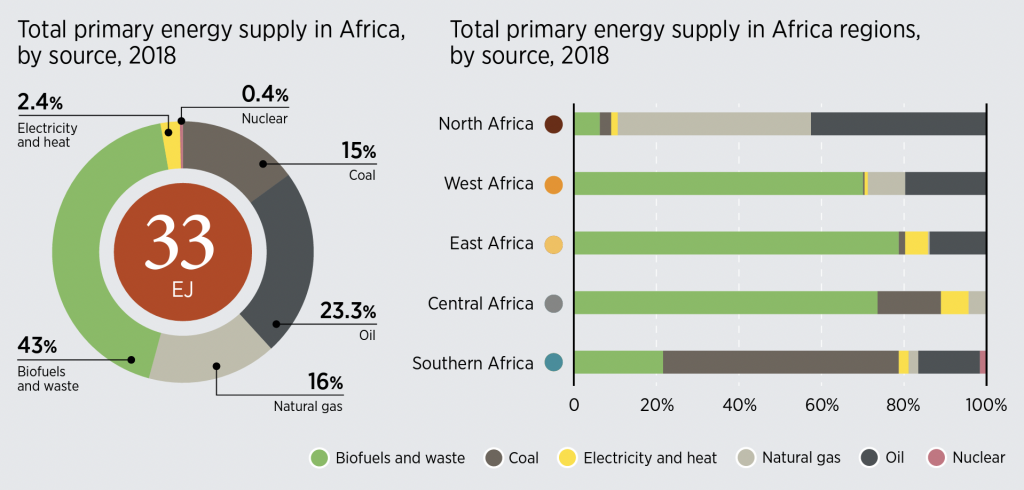

Notwithstanding the sizeable population Africa only contributes a negligible share of global greenhouse gas emissions, and accounts for just 6% of global energy demand and 3% of electricity demand. This is particularly surprising as the main provider of energy in the region is currently wood biomass, and fossil fuels.

Yet centralized fossil fuel infrastructure has not been able to satisfy Africa’s current energy needs and will not be able to do so in the future. On the other hand, renewable energy technologies are emerging as a flexible combination of grid-based, off-grid and mini-grid solutions that can bring universal energy access for all Africans whilst limiting climate-related externalities.

An influential report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Renewable Energy Market Analysis: Africa and its Regions, indicates that Africa is home to around 39% of the world’s renewable energy potential, the most of any other continent, and argues that renewable energy capacity in Africa could reach 310 GW by 2030.

This spark could come from a wide range of renewable sources. According to the African Development Bank Group, Africa has an almost unlimited potential of solar capacity (10 TW), abundant hydro (350 GW), wind (110 GW), and geothermal energy sources (15 GW).

Yet the investment gap in African renewables is still overwhelming, and fossil fuel companies continue to invest heavily in new fossil fuel exploitation in 48 out of 55 African countries.

To add insult to injury many of these fossil fuel extraction projects are not designed to provide direct energy access benefits to the African countries in which they are being developed. For example, 89% of liquified gas infrastructure currently under development in Africa is for gas that is destined to Europe as it seeks to wean itself off Russian exports.

African nations taking the lead

Leaders of African nations took a historic step towards building a clean energy future and addressing climate change on their own terms during the The Africa Climate Summit (ACS) held alongside Africa Climate Week 2023 (ACW) in early September.

Bringing together over 10,000 participants, including leaders and representatives from African governments, multilateral organizations, the private sector, and civil society, the events culminated in the Nairobi Declaration issued by the chair of the African Union Commission in collaboration with the government of Kenya and the COP28 presidency.

The declaration explicitly states a commitment to triple renewable energy capacity and double energy efficiency by 2030, marking a first such unified statement on Africa’s clean energy vision and in the process providing a key starting point for the upcoming COP28 negotiations.

In fact, the Nairobi Declaration has set the target of hosting at least 300GW of renewable energy generation capacity by 2030 (the current amount is 56GW) in Africa, in an effort to achieve both energy access and decarbonisation goals.

“Africa’s untapped renewable energy potential, which is 50 times the global anticipated electricity demand by 2040 can play a significant role in keeping the rise in global temperature within the 1.5˚C objective,” reads the declaration.

James Irungu Mwangi, a Kenyan entrepreneur who helped organize the event, told the New York Times that: “If you think about the attributes and the assets that we’re going to need in order to survive and thrive this century, Africa is uniquely well endowed […] Investing in Africa and climate positive growth is one of the best chances the world has of getting anywhere close to the Paris goals.”

On top of clean energy the declaration also highlights other key themes such as sustainable land use, technology development, carbon credits, the need for collaboration on adaptation measures, and renewed calls for climate justice and financial support to tackle the climate crisis in the region.

$2.8 trillion were invested in renewables globally between 2000 and 2020.

Only 2% went to Africa.

The #EnergyTransition could grow the region’s economy by 6.4% by 2050. @IRENA | @AfDB_Group | #MenaClimateWeekhttps://t.co/0u7JZDZ0MQ

— UN Climate Change (@UNFCCC) January 14, 2022

Kenya’s president William Ruto, who hosted the events, highlighted the historic nature of the event and stated that the global “climate conversation” began in 1992 during a UN summit in Rio de Janeiro, but “this is the first African summit 31 years later”.

Potential but more global efforts needed

Charra Tesfaye Terfassa, a senior associate at the independent climate think-tank E3G, commented in the aftermath of the summit that it had focused excessively on “green growth opportunities”, without questioning the behavior of countries from the northern hemisphere.

This sheds light on a key issue: how to access the funds needed to put a spark in Africa’s renewable energy growth? Promises by wealthy nations to set aside 100 billion USD in climate-related financing are yet to fully materialize, and reforms at the World Bank and International Monetary Fund are long overdue to ensure that developing countries can access loans at below-market interest rates and with more lenient timelines for repayment.

Tom Mitchell, executive director of the International Institute for Environment and Development, highlighted this paradoxical situation at a London conference: “At the moment, we’ve got developing countries paying way more in debt repayments back to richer countries than they ever hope to receive in climate finance or support.”

This means that just as the world races ahead investing more money in renewables such as solar than they have in oil for the first time ever, the African continent is still being priced out due to a loan system that deems the region too risky for investment. For a region with such a high recognized potential for renewables, it is staggering that only 2% of global investment in renewable energy has gone to Africa.

“It’s time to end the net-zero hypocrisy,” says Katrin Ganswindt, finance campaigner at Urgewald. “Net-zero commitments for tomorrow are meaningless if today’s finance keeps flowing into the expansion of fossil fuel production and use.”

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres also echoed this position during the launch of the 2022 Emissions Gap Report: “Commitments to net-zero are worth zero without the plans, policies and actions to back it up. Our world cannot afford any more greenwashing, fake movers or late movers.”

A bright future?

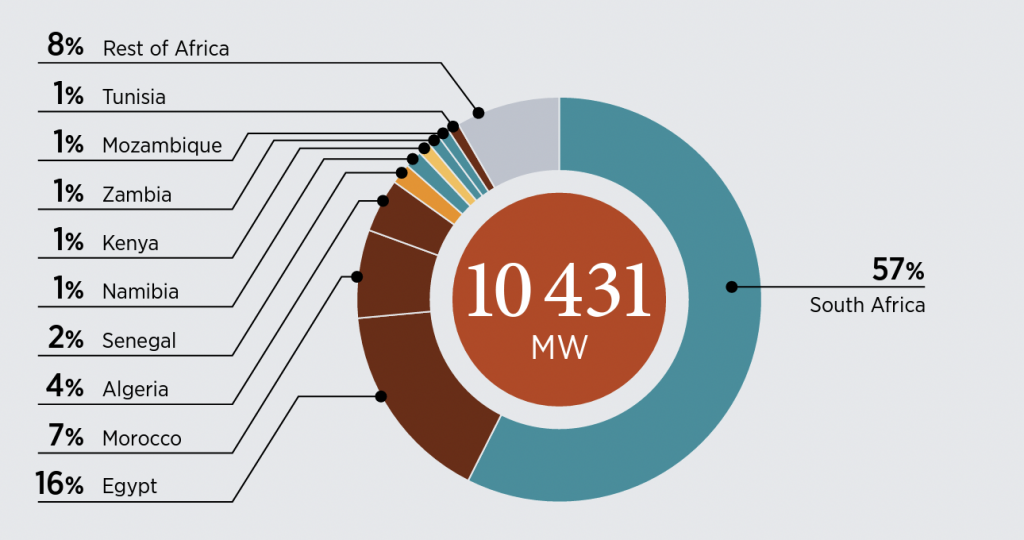

Solar energy in particular is seen as one of the renewable sources with the most potential for the African region. According to the IRENA report, between 2011 and 2020, solar capacity in Africa grew at an average compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 54%, two and a half times that of wind (22.5%), almost four times that of geothermal (14.7%) and almost 17 times that of hydropower (3.2%).

However, utility-scale solar power has been deployed in just a few countries as securing investments remains a major issue.

Archip Lobo, co-founder of Nuru, a company dedicated to enhancing connectivity in the Democratic Republic of Congo, became one of the exceptions this year when he managed to raise 70 million USD in international funds to build solar-powered microgrids in Congo.

“A year ago, we were about halfway to losing hope,” Mr. Lobo told The New York Times. “We were thinking, These lenders all want us to assure them there’s no political risk, no security risk. How can you do that in Congo?”

Research indicates Africa may require up to USD 2.8 trillion by 2030 to meet the emission reduction targets outlined in the Paris Agreement. Achieving this goal will require increases in climate investments by a factor of ten, which is equivalent to nearly 93% of the continent’s current GDP.

However, transitioning to renewables is not just a cost but also an opportunity which, for example, can play a key role in creating jobs. Research indicates that investing in energy transition technologies creates up to three times as many jobs as fossil fuels per million of dollars spent.

Under IRENA’s 1.5˚C Scenario for the period 2020-2050, “every million U.S. dollars invested in renewables would create at least 26 job-years; for every million invested in energy efficiency at least 22 would be created annually; for energy flexibility, the figure is 18. The gains would far outweigh the loss of fossil fuel sector jobs during the transition.”

Although during the Africa Climate Summit countries pledged to increase their investments in the continent, reaching approximately 26 billion USD for climate investment of which the United Arab Emirates alone promised 4.5 billion USD for clean energy projects, wealthy countries have to step up to their promises if renewables are to reach their full potential.

Although Africa is rich in critical minerals for the energy transition, including cobalt used in electric vehicle batteries, and home to 60% of the planet’s best solar resources, the continent is still only receiving 2% of global clean energy spending, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Chavi Meattle, a climate finance in Africa expert at the Climate Policy Initiative, explains that rich countries have “made promises to reform, but they are not following through fast enough.” In a paper on the issue of climate investments in Africa, for which Meattle is a co-author, the funds which have been invested have gone to just a few of Africa’s most advanced economies, like Egypt, Morocco and South Africa, which is further exacerbating inequalities in the region.

Inequalities that are also evident on smaller scales. According to IRENA electricity access is typically higher in urban centers, whereas rural electrification, particularly in many parts of SubSaharan Africa, continues to highlight the urban rural divide: 84% electrification rate in urban areas compared with 29% in rural areas.

Even though the rate of access to electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa rose from 33% in 2010 to 46% by 2019, 570 million people still lacked access to electricity in 2019. If things continue along current trends the target of universal access to modern forms of energy by 2030 spelled out in SDG 7.1 will be missed by a large margin. By 2030, around 560 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa are expected to still be without electricity and over a billion will still lack access to clean cooking fuel.

Cristina Gamboa, CEO of nonprofit World Green Building Council, explains how African cities are uniquely placed to direct Africa’s energy future as populations continue to boom. “Eighty percent of the infrastructure Africa needs by 2050 has not yet been built,” Gamboa said at the IMPACT conference.

“They’ve come to a recognition that it is good development to leapfrog and go into the clean energy transition now.”

What lies ahead

So, is the solution to go cold turkey and stop all investments in fossil fuels to concentrate on renewable energy? According to African Development Bank (AfDB) president Akinwumi Adesina, “We are going to use all the renewable energy sources we have, but they are variable resources. Africa needs stable grids to industrialize. Gas is a very critical part of the energy mix.”

Currently biofuels and waste are still the most widely used sources of energy in the continent, accounting for over 40% of energy supply, with oil the second largest source of primary energy, particularly in transport, industry and power generation.

Yet countries, such as Kenya, offer a glimpse at what a successful clean energy transition could look like. Kenya Electricity Generating Co., the East African nation’s main power producer, plans a 1,000 megawatt wind farm that would be the continent’s biggest such facility, and currently 92% of Kenya’s generating capacity comes from renewables with the government pledging to increase that share to 100% by 2030.

Although the potential for a renewable energy revolution in there, the key spanner in the works continues to be Africa’s energy finance gap, which requires a concerted effort by investors in Africa’s energy markets and governments, as well as global development partners.

The direct link between Africa’s energy finance gap and the long-run scenario for the global climate crisis has to be made, and in that way further motivate investors to put their money where their mouths are.