From early childhood we learn that around 70% of planet Earth is made up of water. This amounts to around 1,390 billion km3 of which 97.5% is the saltwater contained in our seas and oceans. Only around 2.5% of Earth’s water is freshwater which is the essential building blocks for life as we know it.

The majority of freshwater is stored in the polar ice caps and glaciers. In fact, humanity only has direct access to around 0.5% of the planet’s fresh water, of which only a part is clean and safe for drinking.

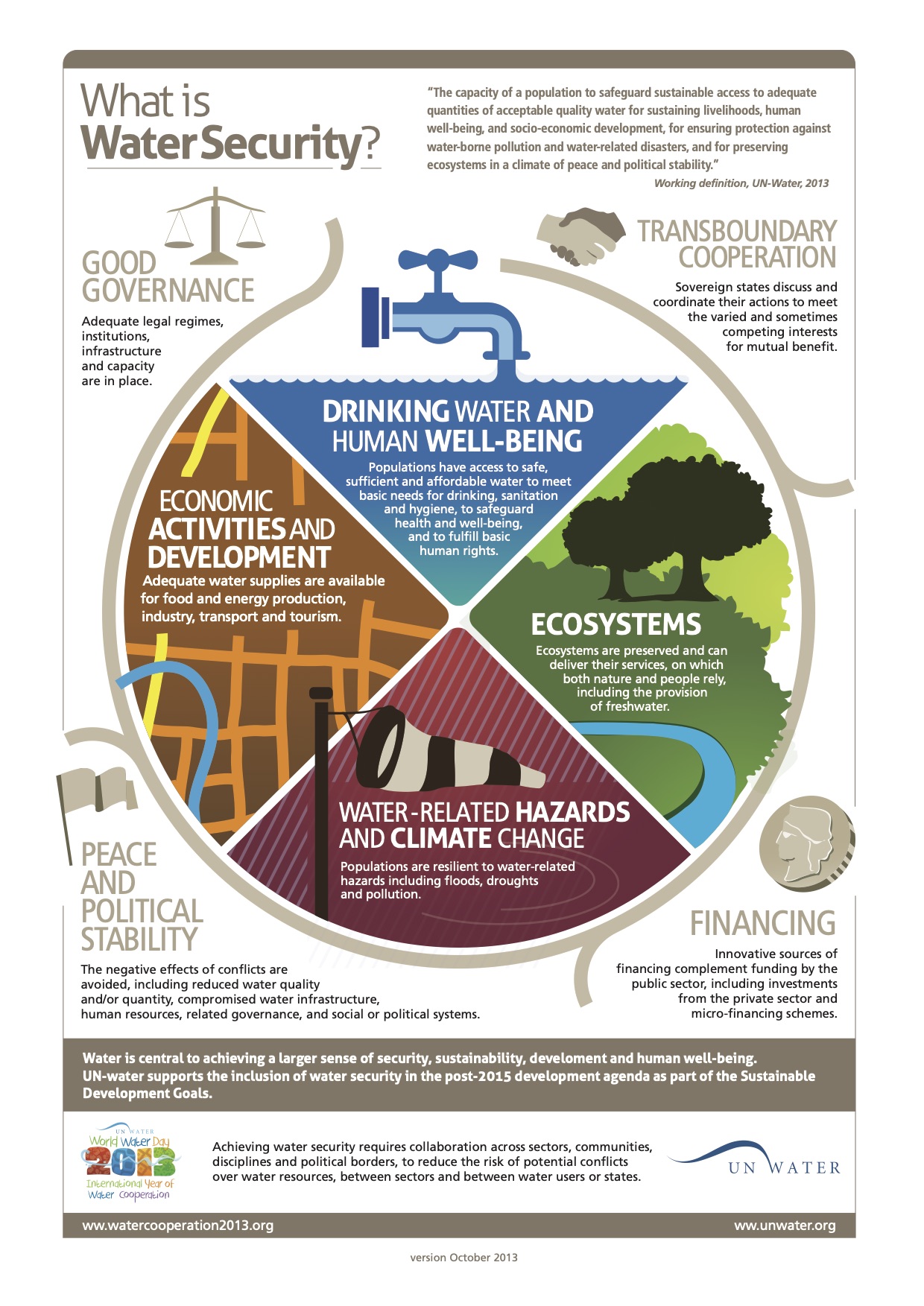

Water security is essential to sustainable development – enshrined in Sustainable Development Goal 6, Clean Water and Sanitation – and access to adequate quantities of acceptable quality drinking water is the backbone of human well being, socioeconomic development and preserving ecosystems in a climate of peace and political stability. Ensuring access to clean and safe drinking water is a major concern around the globe particularly as population levels continue to rise and climate change intensifies.

Why glaciers are important for water security

Melting and shrinking glaciers are one of the most tangible effects of climate change on water resources. They give a visual representation that is hard to ignore and – particularly in tropical and subtropical regions – glaciers act as storage tanks for freshwater whereby they compensate for seasonal variability in the flow of mountain rivers by providing a constant and reliable input of meltwater.

As glaciers continue to shrink and retreat their role as water reservoirs is changing. For example, their contribution to river flows initially increases with more rapid melting and then diminishes as less ice remains. This affects the livelihoods of both mountain communities and those that live downstream, leading to competition for the resource and potential conflicts.

The SDG 6 Progress Update shows we are seriously off-track to ensure sustainable water and sanitation for all by 2030.

It is time for actions. It’s time to roll up our sleeves. #SDG6 is critical and a catalyst for the entire #2030Agenda.#WorldWaterDay https://t.co/z7eSaMUCP4— UN-Water (@UN_Water) March 18, 2021

“Research has revealed that these changes in mountain river stream flow are already happening. Global assessments of glacier extent and thickness have shown that several smaller tropical glaciers are on the verge of disappearing or beyond the peak flow caused by their melting. As glaciers shrink, they will provide a smaller contribution to the overall river flow,” explains Dr Wouter Buytaert, Grantham affiliated Lecturer in Water Resources and Environmental Change in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Imperial College London.

Melting glaciers affect water security

In Latin America, the impacts of melting glaciers on high altitude communities living in countries such as Peru and Bolivia are well documented. “Because of their remoteness and difficult living conditions, inhabitants of mountain regions are particularly vulnerable to the degradation of natural resources,” explains Buytaert.

Research indicates that water resources in La Paz and El Alto, Bolivia, strongly depend on runoff from mountain catchments in the Cordillera Real, Andes. The impacts of rising demand due to growing populations and runoff variability due to climate change have caused acute water crises in recent years.

Furthermore, experts predict that by 2036 water demand in the region will increase by anywhere between 15-53% compared to that of 2011, whilst at the same time water supply will be subject to significant reductions because of the climate variability and decreasing glacial meltwater.

Similar problems are also being experienced across the Himalayas. Scientific evidence indicates that the majority of glaciers in South Asia’s Hindu Kush Himalayan region are already retreating. Although the consequences that this will have on the region’s water supply remain unclear there is growing concern that the retreat will affect important river basins in the region that supply fresh water for over 1.5 billion people causing unrest and conflicts downstream.

https://t.co/kR331sWz7C

Water shortages may loom in the future of 1.3 billion people living downstream from the Himalayas in Nepal, due to climate change, says new research from Ball State University.— Climate Change World Media Newshub 24/7 (@GNewshub) May 24, 2020

Yet the problems of water security due to glacial melting is not just restricted to developing countries. In New Zealand, the Brewster Glacier in New Zealand’s Southern Alps lost around 13 million cubic metres of ice between March 2016 and March 2019 – which amounts to the basic drinking water needs of all New Zealanders during that time.

Overall glaciers in the country’s Southern Alps’ are believed to have lost more than 30% of their volume – about 16 billion cubic metres of ice, or the equivalent of about 200 litres a day for each New Zealander over 40 years.

Even the European Alps are not exempt and are increasingly showing signs of vulnerability to the effects of climate change. Since 1850, the Alps have already lost half of their ice volume, 17% of which occurring since the turn of the century. By 2050 Alpine glaciers below 3,500 metres above sea level will lose their accumulation areas which implies that – in time – they may well disappear. Studies even indicate that the Alps are expected to lose over half of their total ice volume by mid-century if CO2 emissions stabilise – with even graver consequences ahead if we continue to increase emissions.

The future of glaciers

Earth’s great expanses of water and ice, which are fundamental components of the planetary ecosystem, have already registered huge and irreversible changes. According to the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC), global warming is responsible for the widespread shrinking of the world’s cryosphere, leading to significant reductions in the ice mass of both ice sheets and glaciers.

The Summary for Policymakers for the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (#SROCC) 🌊 is now available in all UN languages:

📘 https://t.co/INhkFDKDKr

🇬🇧 🇫🇷 🇨🇳 🇪🇸 🇦🇪 🇷🇺 pic.twitter.com/fZ9bWfSAen— IPCC (@IPCC_CH) July 7, 2020

Even under a conservative emissions scenario, whereby atmospheric CO2 levels stabilise by the end of the century, the European Alps are expected to be deprived of around two-thirds of present-day glacier volume and area. In contrast, pessimistic warming scenarios – outlined in a 2019 study – indicate that the Alps may even be almost entirely ice-free by 2100.

“Although we will still lose many parts of big glaciers due to the current imbalance with the present climate, we can save at least some parts of glaciers if we stay below 2 degrees warming,” explains Michael Zemp, professor at the University of Zurich and Director of the World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS).

The melting of glaciers will have a long-term impact not only on the mountain valleys and lower-lying regions. Consequences will be felt throughout countries and across borders. Today, 1.42 billion people – including 450 million children – already live in areas of high or extremely high water vulnerability. Understanding the impact of melting glaciers on water security can provide valuable information for water management and an added incentive for lowering emissions and an integral part of this is studying and documenting the retreat of glaciers.

Sustainable development needs water security

Melting glaciers are just one of the problems affecting water security. In fact, ensuring the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all is one of the building blocks of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and enshrined in SDG 6.

The growing threat of water stresses across the globe has far-reaching consequences on economic development, food security, health, ecosystems, energy production, poverty eradication and gender equality.

The recently launched SDG 6 Summary Progress Update 2021 report includes updated country, region and world data on all of the SDG 6 global indicators. It gives a snapshot of the progress we have made in reaching SDG 6 around the world as well as an indication as to where we need to step up efforts if we are to achieve sustainable water and sanitation for all by 2030.

In 2021 it appears that we are still far off the mark and the world is currently not on route to meeting the targets of SDG 6. Only ten years remain to achieve these goals which means we must establish an immediate and integrated global response to rapidly improve progress on SDG 6.