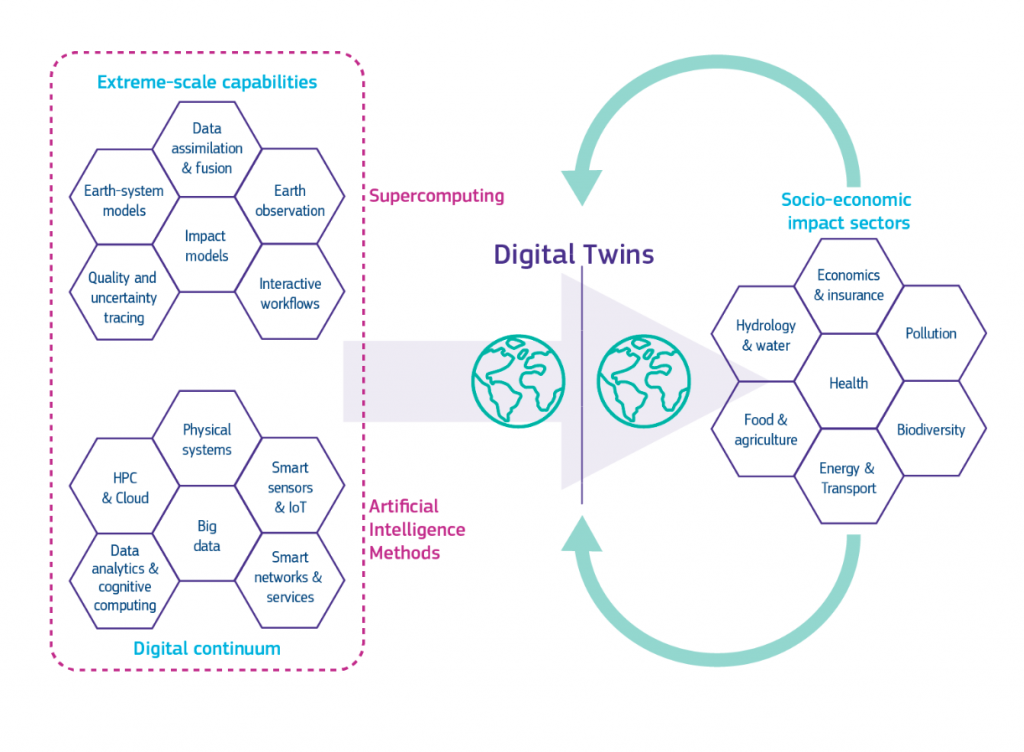

High-performance computing is already playing a vital role in creating the models and simulations that lay bare the realities of climate change on a global level. At the same time, there is an ever-growing need to provide detailed and accessible information on how a changing climate will impact local systems, projects, and communities, including the daily lives of individuals and their assets.

Enter digital twin: virtual and dynamic models of real-world objects, machines, or systems that are composed of both a digital simulation and live sensor data from the real world that keep the model up to date.

“The definition of digital twins is that they have a full cyclic interaction with information: the digital world interacts with the real world and vice-versa,” explains Dr Peter Bauer, Director of Destination Earth at the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF).

“Digital twins are interactive systems where you can change things in the digital world, which in turn helps you plan, define and operate assets in the real world such as dykes, wind farms, or flood dams,” Bauer continues.

Although digital twins have, thus far, mainly focused on industrial applications, scientists are now looking to deploy them in relation to climate change research, with the potential for far-reaching benefits.

The goal is to create digital replicas which can provide more specific, localized and interactive information on climate change and how to deal with its impacts.

A digital twin of our climate system

At a European level the Destination Earth (DestinE) project – a joint effort between the European Space Agency, the European Organization for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites, and the ECMWF – is working to create a highly accurate digital model of the Earth to monitor and predict the interaction between natural phenomena and human activities.

“DestinE will improve our understanding of climate change and enable solutions at a global, regional and local level. For example, the digital modeling of the Earth will help to predict major environmental degradation with unprecedented reliability,” explains Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President for a Europe fit for the Digital Age, in the European Commission’s press release.

The idea is to create the best possible rendition of the real world so that it can then be used to design physical assets that are able to address given climate issues, speeding up both the discovery and implementation of solutions.

“With regards to climate change, digital twins can – for example – help plan and define future renewable energy generation, including where to place these systems and how to make them safe with respect to future climate extremes,” explains Bauer.

Scientists hope these digital models will help a variety of stakeholders understand climate impacts both now and in the future, allowing them to test different scenarios which can range from the ability of sea barriers to prevent flooding to how reservoirs can help local communities deal with future water scarcity.

“We need to create an interconnectivity with models whereby you are already generating information that is focused on specific applications,” explains Bauer.

In practical terms, this means turning things like weather data into flooding information or wind predictions into energy potential. Leading to data sets that are already focused on specific applications so that you don’t stop at predicting weather in terms of precipitation but that you tie model components into that system to produce use case-specific information.

A matter of scale

One of the key differences between digital twin and simulation comes down to scale: whereas a simulation typically studies one particular process, a digital twin can look at any number of useful simulations and therefore address multiple processes at the same time: from modeling industrial equipment, cars and bridges to the human body and the overall climate systems.

“Different data and different simulations represent different scales, but if you can subset a global system with a regional system focused on a specific application, such as pollution over Bologna or agriculture in Puglia, for example, then you can break down the global information that drives that regional system, which then boils down to specific applications,” says Bauer. “Think of it as a hierarchy of systems and as you work your way down these systems you narrow down your focus.”

However, this presents a key challenge which revolves around turning the large quantities of data generated into accessible and useful information.

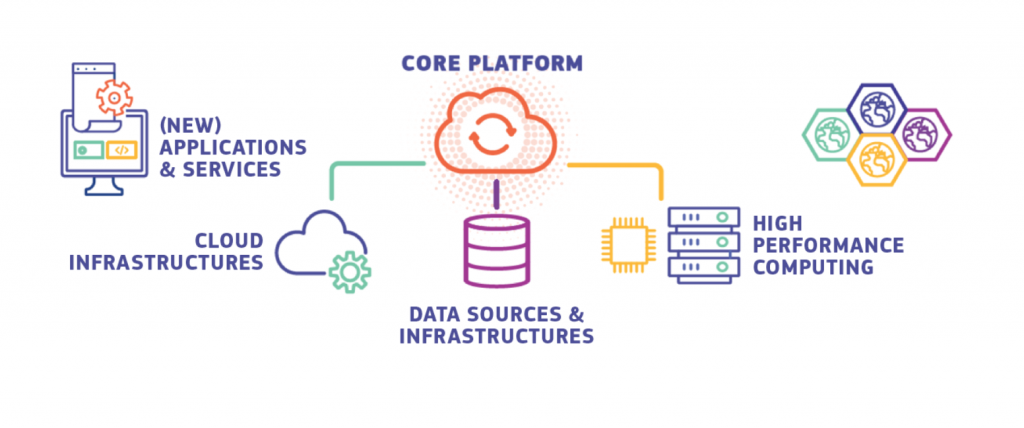

Part of the DestinE project is Digital Twin Ocean, led by the non-profit organization, Mercator Ocean International (MoI), in collaboration with CMCC Foundation, IFREMER, the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI), and the University of Bergen (UiB).“Our objective is to make complex ocean information simple to use. State of the art ocean observations and monitoring combined with advances in high performance computing, big data, Internet of Things, and digital twins will help use design a drastically new digital ocean,” says Pierre Bahurel, Director General of MoI during a video statement for the GEO week.

The project also involves developing the Blue-Cloud demonstrator “Marine Environmental Indicators”, an online service with an associated cloud-based analytical computing framework and a dedicated web interface that brings together information and data on the current state of the ocean.

This Blue Cloud feature is important as it can help a variety of stakeholders, including both researchers and policymakers, access the specific information they are looking for more easily.

Digital Twin Ocean would therefore become a powerful asset to support the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development and the 2030 Agenda, by helping stakeholders explore the impacts that management decisions such as reducing CO2 emissions or establishing marine protected areas would have on marine ecosystems, climate, and ocean economy sectors.

An objective Bauer is also quick to highlight with reference to DestinE: “it will bring two main innovations in the way we look at climate issues. Firstly, in the quality of data and secondly in the configurability and ability to interact with large amounts of data and models.”

This would be a key innovation as, currently, if you want to use complex earth system satellite data you have to access given data websites that have few tools to help non-scientific experts extract and interact with the relevant information.

However, with the digital twin, you will be able to interact with a virtual world that hides away a lot of the technical complexities. The convenience of interaction is therefore one of the main goals and this will make information and interaction with digital twin models more accessible to a plurality of stakeholders.

Although full-scale digital twins of the earth and ocean are yet to be deployed, and significant bottlenecks remain – particularly with regards to both a need for more observational data and the processing of huge amounts of data particularly when refining the scale of investigation – researchers believe that they will soon be able to provide clearer and more accessible information on the problems associated with climate change.

“I hope that this new way of interacting with the earth system can help communicate the overall problems related to climate change more easily and draw interest in DestinE and digital twin development, particularly among the younger generations,” concludes Bauer. “There are enormous opportunities in this field and we want to mobilize the younger generations to come along with us and contribute.”