When you think about change you are thinking about the future. As the climate is changing due to human influence resulting from past choices, what we do today has the power to shape many possible futures.

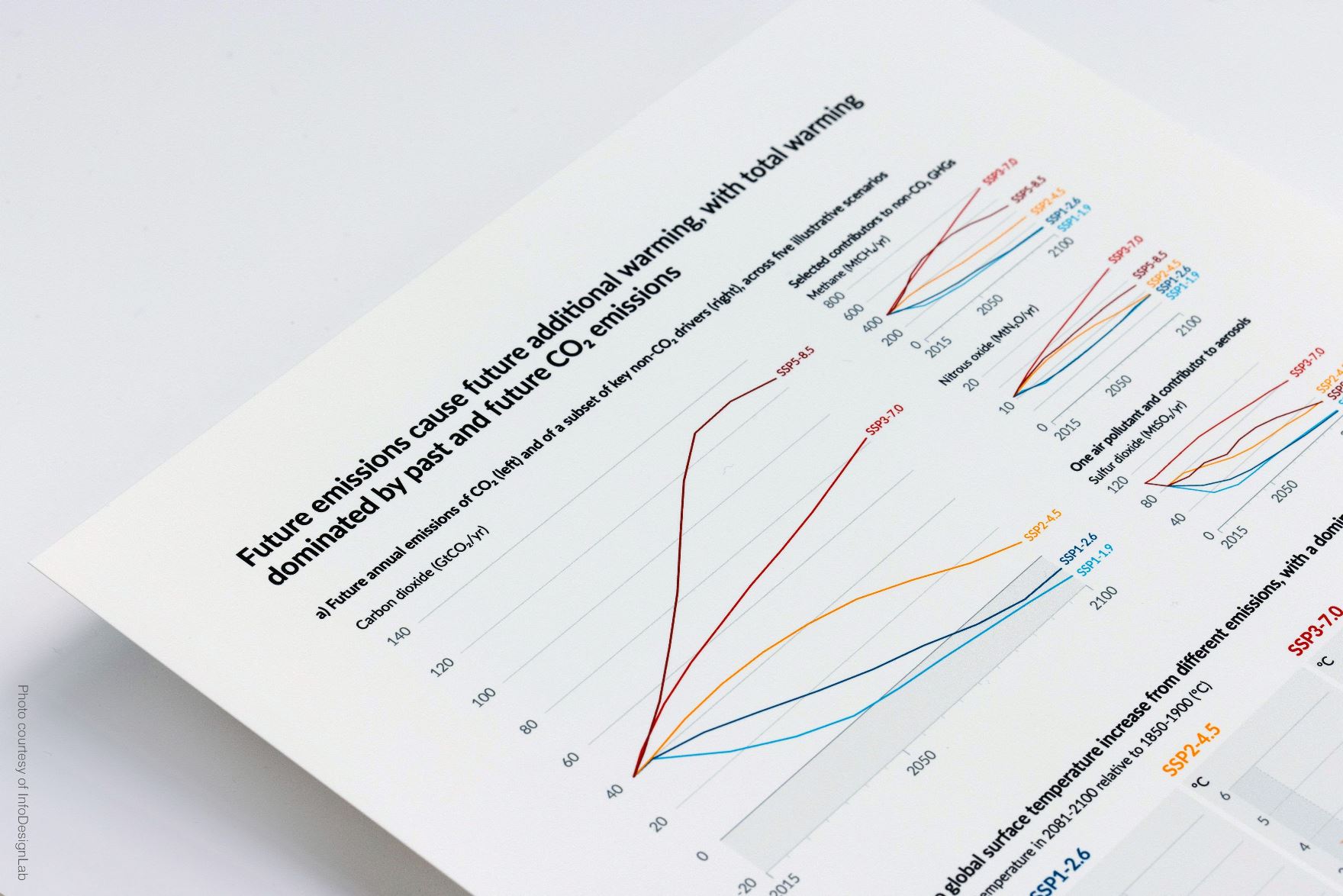

Scenarios are alternative images of how these futures may unfold. “Coherent, internally consistent, and plausible descriptions of possible future states of the world,” according to the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, whose Sixth Assessment Report considers five different scenarios. Five possible futures, ranging from the worst-case scenario, that describes a world without climate action and characterised by a fossil-fuelled development, to the most optimistic and ambitious one. In the best possible future, the world will shift toward a more sustainable path, reaching the net zero goal by 2050 and meeting the Paris Agreement target of not exceeding the 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming by the end of the century.

Scenarios are imaginations of futures and their mathematical translations.

Massimo Tavoni, Director of the RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment

“Scenarios are imaginations of futures and their mathematical translations. Mostly in terms of climate change, but also in terms of consequences for society, for health, for well-being, for energy, for technologies, and for many other aspects,” says Massimo Tavoni, director of the RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment and a lead author of the 5th and 6th Assessment Reports of the IPCC, in his conversation with the science and data journalist Elisabetta Tola during the Voices of the transition. Climate change communication for a sustainable future event organised by the CMCC Foundation.

Many social and economic dimensions are linked to different emissions trajectories, from regional rivalry to inequalities, from education to technological development, from population growth to health and wealth. Under the name of Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP), the latest IPCC report shows five different narratives of the future, which identify alternative socio-economic developments.

“As scientists, we use data, numbers and models: a very empirical approach to try to make projections for the future,” explains Prof. Tavoni. “But we recognize that, by using data from the past, we can only imagine certain futures. Instead, what we are looking at is a future which is very different from the past. How can we imagine futures which are different from the past, if the only data that we have is data from the past?”

“Of course, there are some data and histories from the past that could be useful in understanding possible futures,” continues Tavoni. “But we also need imagination. We are not making projections: what we are interested in is thinking about what the consequences of certain futures would be. Therefore, we ask experts what their opinion about the future is. We imagine many different futures with the help of experts, and for each of these different futures we try to understand what the challenges and the consequences would be.”

Climate scenarios, says Tavoni, are translated by professionals in visualizations and tools that simplify their use for policymakers and society at large, thus managing to cross the boundary of the scientific sphere. An example of their application is the recent “Risk Analysis. Climate change in six Italian cities”, in which the expected climate for Italy in the coming decades is described by CMCC researchers at a city level, according to two alternative scenarios.

This is how science can reach decision-makers and actors at different scales, an therefore be understood, applied and useful for everyday life.

“We are depicting bad futures so that people understand the consequences of the climate crisis if we do not work on it,” adds Tavoni as he talks about both scientists and the long tradition of science fiction and its inclination to make use of two extreme narratives, describing either dystopian or utopian futures.

“We also need something in between. What we should also work towards – and this is more challenging from a science communication perspective – is make people think about a good future. Hopefully, the earth is going to be clean in 20 or 30 years from now. If you think about a future like this, and you try to think about yourself in that future, you will not want to go back. Maybe this message is not going to sell a lot of books, but it would help policymakers enact ambitious policies, as we would show them that the road to a climate-safe society is going to be bumpy, but it is going to lead us to a much better future.”

Watch the conversation between Massimo Tavoni, Director of the RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment, and Elisabetta Tola, science and data journalist at Radio 3 Scienza, at the event Voices of the transition. Climate change communication for a sustainable future.