Climate change is increasingly affecting multiple aspects of human health and well-being, generating risks for global health such as the emergence and diffusion of vector-borne diseases, water scarcity and food insecurity. These threats affect people globally with different intensities based on geographic and demographic patterns, and have a strong impact on global-scale phenomena such as migration patterns, the production of goods, and the economy.

Furthermore, the impacts of climate change on human health are not felt equally: vulnerable members of society such as women, the elderly and economically disadvantaged people are often the most at risk.

In an effort to provide an up to date picture of the relationship between climate change and health, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) examined the impacts of climate change on “Health, Wellbeing and the Changing Structure of Communities” in the 2022 Working Group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report “Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability”.

According to the report, climate-related illnesses, premature deaths, malnutrition, and threats to mental health are increasing. Moreover, climate hazards are driving migration and displacement and contributing to conflicts. These impacts are interconnected and unevenly distributed, leading to inequitable experiences due to differences in exposure and vulnerability of different populations. There is strong evidence of cascading and compounding health risks from extreme weather events, with expectations of increased risks as global warming continues.

“Human health and the health of our planet are inextricably linked, and our civilization depends on human health, flourishing natural systems, and the wise stewardship of natural resources. With natural systems being degraded to an extent unprecedented in human history, both our health and that of our planet are in peril.”

Planetary Health, stands for United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

For instance, air pollution is one of the most evident environmental threats to human health.

As reported by the World Economic Forum (WEF), many low- and middle-income countries lack air quality monitoring and effective emission control legislation, leading to amplified health impacts.

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported over 4 million annual deaths, allegedly caused by indoor biomass fuel and coal burning for domestic heating and cooking. By 2018, over 80% of people living in urban areas are reported to have faced air quality levels above WHO limits, with 49% of large cities in high-income countries and 97% of large cities in low- and middle-income nations failing to meet guidelines.

To mitigate the effects of climate change on health, well-being, migration, to reduce disease rates, and lower mortality, it is imperative to implement additional adaptation measures at a global level. International agreements such as the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals offer potential solutions and establish pathways and targets to tackle the challenges and guide common action.

According to the IPCC, proactive adaptation measures can reduce and potentially avert many health-related climate risks, but a significant adaptation gap remains. Although there’s evidence of multi-sectoral collaboration, financial support for health adaptation remains inadequate.

Climate-resilient development can yield co-benefits for health and well-being, diminishing displacement and conflict risks. Crucially, transformative changes are required to foster climate-resilient development, emphasizing local knowledge, addressing gender-specific vulnerabilities, and ensuring universal access to primary healthcare.

Climate change exacerbates environmental hazards for human health

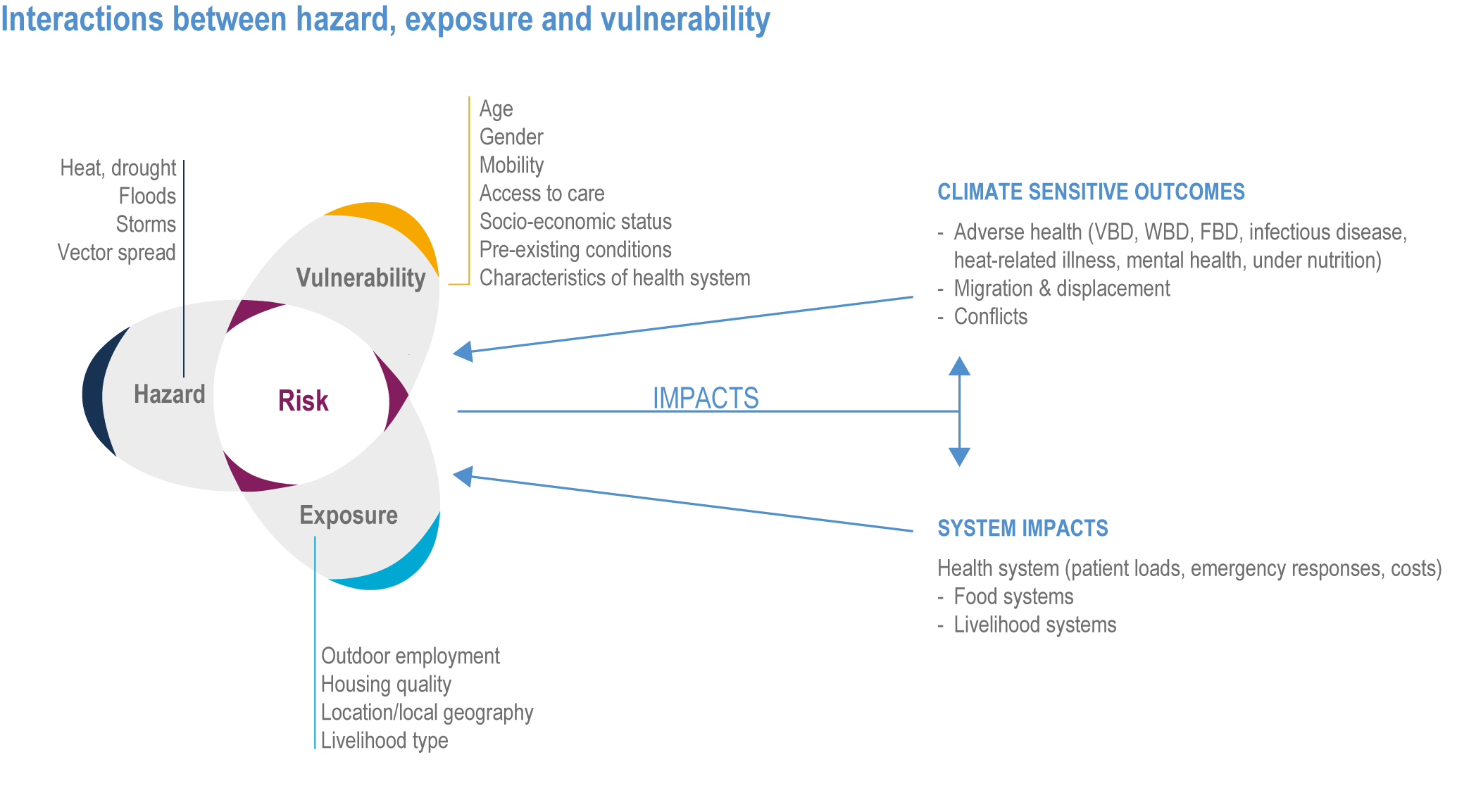

Climate-induced risks for human health can be expressed as the result of an interaction between climate hazards, people’s vulnerability and exposure. As highlighted by the IPCC, the impacts of climate change that can affect health outcomes and health systems have in turn the potential to reinforce vulnerability and/or exposure to risk.

WBD: waterborne disease, VBD: Vector-borne disease, and FBD: Food-borne disease. Source: IPCC

According to a report by the WHO, climate change is the single biggest health threat facing humanity, causing around 13 million deaths every year.

Different environmental hazards have adverse effects on human health, ranging from air pollution and extreme weather events to conditions favouring the spread of infectious diseases. As highlighted by ClimaHealth, a global open-access platform developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Meteorological Organization (WMO), these hazards are significantly exacerbated by climate change.

Extreme heat and extreme cold, for example, are serious threats to human health. In particular, as reported by ClimaHealth, climate change is causing a rapid rise in extreme heat exposure worldwide, leading to heat-related health issues. Heat stress, a primary cause of weather-related deaths, worsens existing conditions like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, psychological distress, and asthma. Additionally, high temperatures elevate accident and infectious disease risks. Both extreme heat and human exposure are increasing, driven by more frequent, intense, and prolonged heatwaves, which can be considered among the most hazardous climate events.

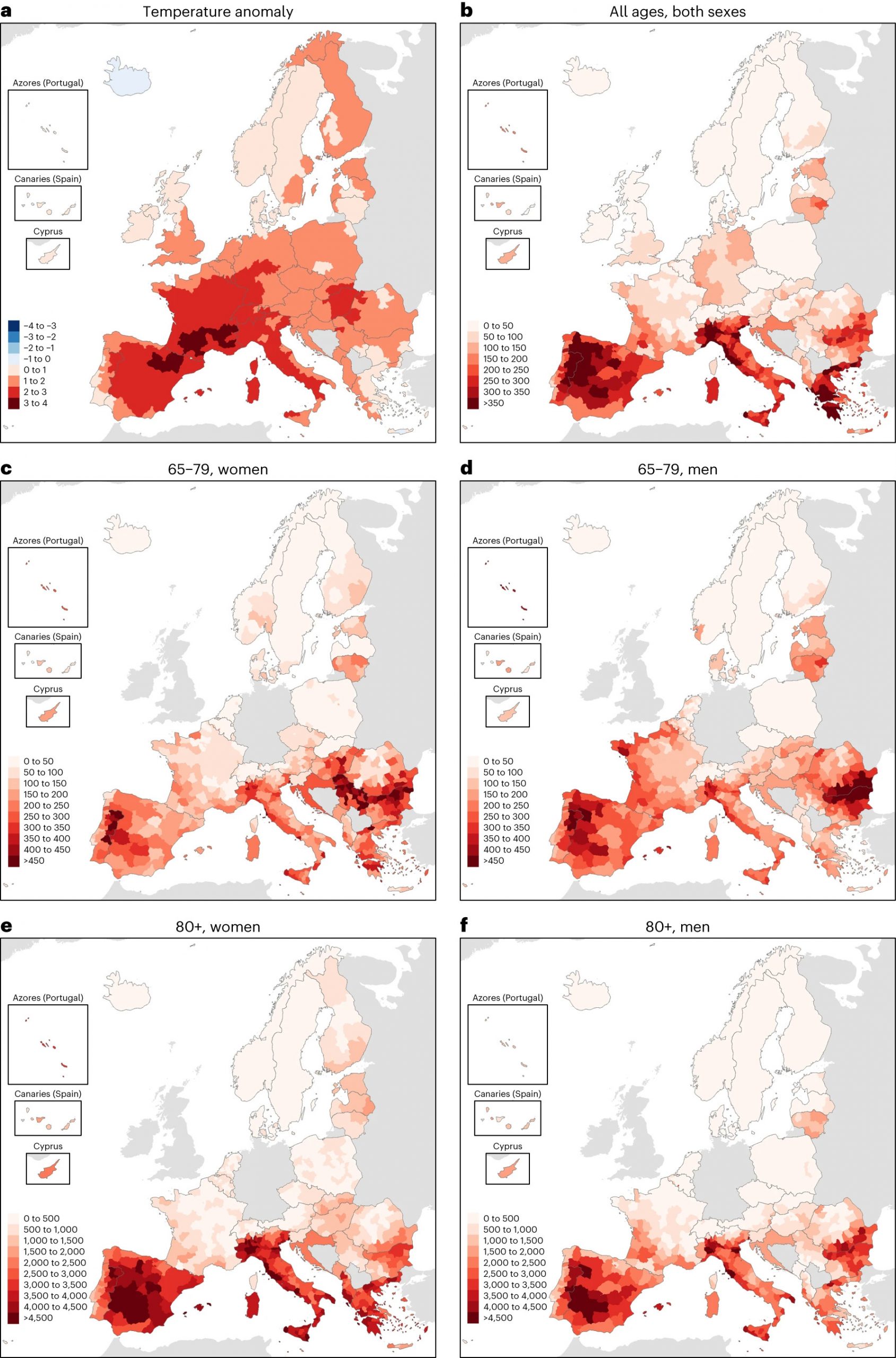

A recent study published in Nature Medicine revealed that over 61,000 individuals lost their lives in Europe in 2022 due to extreme summer heat, with Southern European nations like Italy, Spain, Greece, and Portugal being the most severely affected. The results also showed that mortality rates were particularly high among women and older individuals.

Extreme weather events such as wildfires, droughts, storms and severe floodings are becoming more frequent as a result of climate change, and their impact on human health is equally increasing.

As reported by ClimaHealth, over two billion people globally face high water stress, and around 4 billion (that is, half the world population) deal with severe water scarcity for at least one month a year. This can worsen health inequalities and impact food security, migration, and mental well-being, especially in marginalized areas. Between 1960 and 2020, a total of 724 documented droughts impacted 2.7 billion people, causing 2.2 million fatalities and economic losses amounting to 182 billion US dollars, on a global scale.

According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), approximately 1.8 billion people will face critical water scarcity by 2025, while two-thirds of the global population will be living with water stress due to factors such as drought, climate change, and heavier water consumption.

ClimaHealth reports that climate change is leading to larger, more frequent, and longer-lasting wildfires, exposing more people, even those living far from the fires, to harmful and prolonged levels of wildfire smoke. This is made up of a mix of various chemical compounds that can potentially have harmful effects on health causing respiratory and cardiovascular issues. According to the WHO, around 339,000 people worldwide die as a result of wildfire smoke every year.

Floods, the most common natural disasters, happen when excess water from heavy rainfall, quick snowmelt, or storm surges covers normally dry land. As reported by ClimaHealth, floods are extremely destructive events that often result in loss of life, livelihoods and infrastructure, with disruption of basic services and consequent negative impacts on public health.

Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of floods, and their impacts are exacerbated by land use changes and increased population pressure on flood-prone areas. Flooding affects millions of people worldwide, and the OECD estimates that they cause more than $40 billion in damage each year around the world.

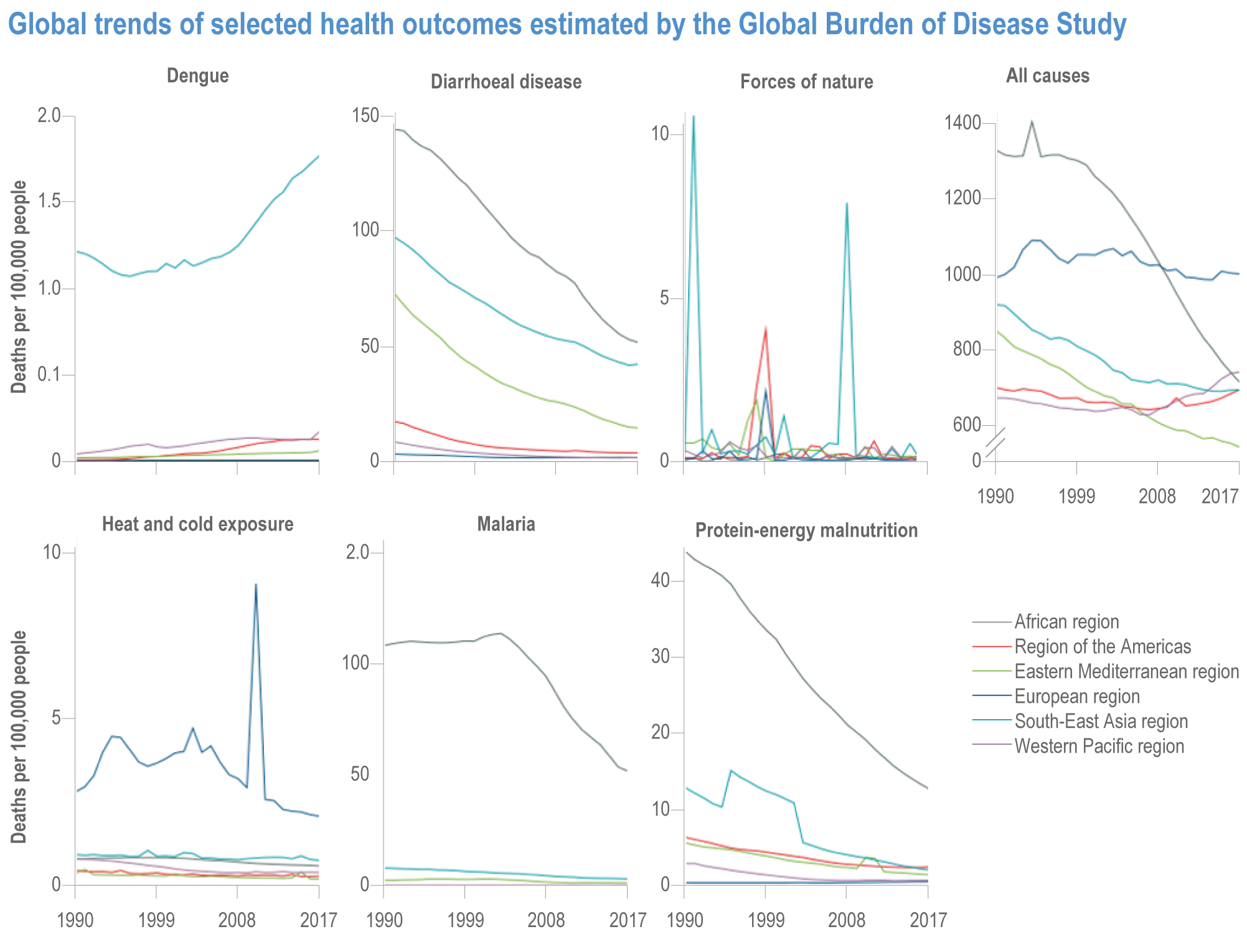

As reported by ClimaHealth, the emergence and spread of vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue is strongly influenced by environmental conditions such as temperature, rainfall and humidity. Therefore, climate change is increasingly affecting the distribution and transmission of many infectious diseases, due to warmer temperatures and more favorable climate conditions for the spread of viruses.

For example, according to the 2022 Global Report of the Lancet Countdown, the transmission season for malaria is now extended in duration by 31.3% and 13.8% in the highlands of the Americas and Africa, respectively, in the period 2012–2021 compared to 1951–1960.

According to the Panel’s WGII report, “the global magnitude of climate-sensitive diseases was estimated in 2019 to be 39,503,684 deaths (69.9% of total annual deaths).” Of these, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases represent the largest proportion of climate-sensitive diseases, with a strong increase of cardiovascular mortality.

Impact and future projections

Extreme weather and climate change affect people all over the world, but some groups tend to be more vulnerable than others in regards to health impacts. According to an article by The Conversation, older adults, and especially older women and people with disabilities, tend to be the most vulnerable to climate-related health risks.

With climate change leading to more frequent and intense weather extremes, and a global population that is aging rapidly, this presents a significant worldwide challenge. By 2030, an estimated one in six people will be 60 or older, increasing to 2.1 billion by 2050. Many older individuals, particularly in the global south, lack the necessary physical, mental, social, and financial resources to mitigate the impact of extreme weather events, leading to an alarming rise in heat-related deaths among this age group. For example, in Europe the summer of 2022 was marked by more than 9,000 heat-related deaths for people aged 65-79 and around 37,000 for those aged 80 and above.

As highlighted by the IPCC, specific demographic groups such as women and girls, and children also are subject to a “heightened vulnerability to climate-related impacts on health and well-being”. This is connected to higher exposure to the risk of water and food scarcity and a stronger vulnerability to heat, infections and air pollution.

Moreover, the report highlights how “people living in poverty are more likely to be exposed to extreme heat and air pollution and have poorer access to clean water and sanitation, accentuating their exposure to climate change-associated health risks.”

Finally, the IPCC report focuses particularly on indigenous peoples, especially those living in geographically isolated and/or impoverished communities, who often experience greater risk of climate-related health impacts.

As reported in an article by the World Bank, around 132 million people will be dragged into extreme poverty by climate change by 2030, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In this context, the World Bank is working on tools to figure out how much it would cost the world not to take action on climate change and its impact on health.

Initial estimates show that health costs related to climate change could already be as high as 1% of the total economy, and this cost could become much larger in the future if the world proceeds with “business as usual”.

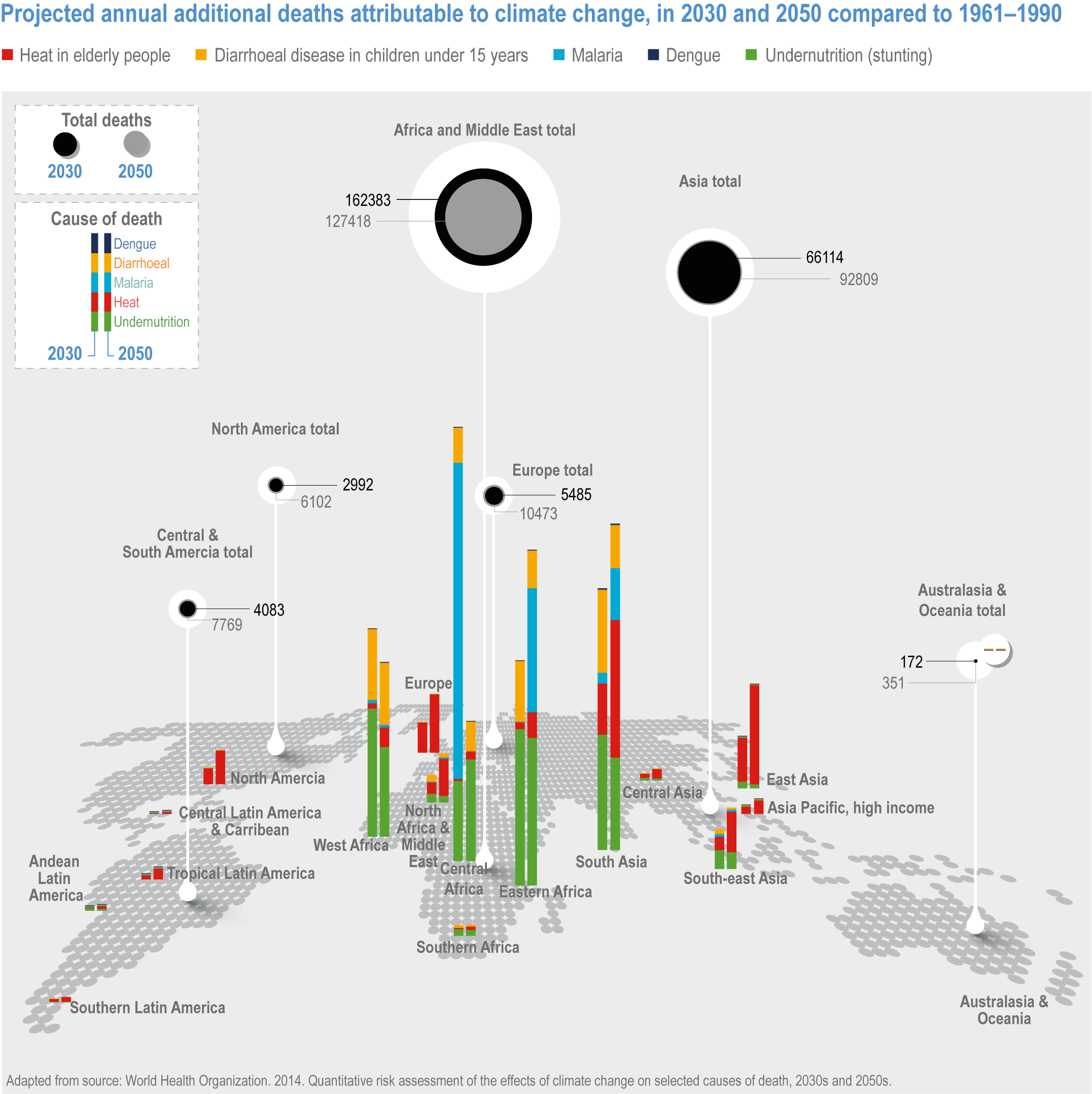

According to the IPCC, the proportion of the overall global deaths caused by climate-sensitive diseases and conditions will increase by mid-century, with high confidence in every scenario. As stated in the WGII report, “climate change is expected to significantly increase the health risks resulting from a range of climate-sensitive diseases and conditions, with the scale of impacts depending on emissions and adaptation pathways in coming decades.”

The report estimates that by 2050 climate change could lead to an excess of approximately 250,000 deaths per year, composed mainly by increases in deaths due to heat and childhood undernutrition and infectious diseases, and mostly affecting Africa for more than half of the overall excess mortality.

“We are facing a profoundly urgent time… Climate change is the single greatest threat to humanity. And the way we experience that primarily and most intimately is through health. I think that we don’t do enough to acknowledge that as a global community or to recognise or remedy that.”

Vanessa Kerry, co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of Seed Global Health and WHO Director-General Special Envoy for Climate Change and Health.

More information:

- The urban divide: unequal distribution of heat-related risks on city dwellers

- Tracking the health effects of climate change around the world – Wellcome

- The 2022 Global Report of the Lancet Countdown

- ClimaHealth platform

- Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report – Chapter 7: Health, Wellbeing and the Changing Structure of Communities

Credits:

- Figure 1: Figure 7.4 in Cissé, G., R. McLeman, H. Adams, P. Aldunce, K. Bowen, D. Campbell-Lendrum, S. Clayton, K.L. Ebi, J. Hess, C. Huang, Q. Liu, G. McGregor, J. Semenza, and M.C. Tirado, 2022: Health, Wellbeing, and the Changing Structure of Communities. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1041–1170, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.009

- Figure 2: Ballester, J., Quijal-Zamorano, M., Méndez Turrubiates, R.F. et al. Heat-related mortality in Europe during the summer of 2022. Nat Med 29, 1857–1866 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02419-z

- Figure 3: Figure Box 7.2.1 in Cissé, G., R. McLeman, H. Adams, P. Aldunce, K. Bowen, D. Campbell-Lendrum, S. Clayton, K.L. Ebi, J. Hess, C. Huang, Q. Liu, G. McGregor, J. Semenza, and M.C. Tirado, 2022: Health, Wellbeing, and the Changing Structure of Communities. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1041–1170, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.009

- Figure 4: Figure 7.8 in Cissé, G., R. McLeman, H. Adams, P. Aldunce, K. Bowen, D. Campbell-Lendrum, S. Clayton, K.L. Ebi, J. Hess, C. Huang, Q. Liu, G. McGregor, J. Semenza, and M.C. Tirado, 2022: Health, Wellbeing, and the Changing Structure of Communities. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1041–1170, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.009