Climate change and human health are interconnected, and their interlinkages are becoming a growing and recognized global concern. From extreme weather events – such as heatwaves, floods, storms, and wildfires – to vector-borne diseases, from food and water security to economic impacts, there are many ways in which climate change is threatening human health.

Scientific literature shows that climate related impacts do not affect everyone in the same way: instead, they reflect socio-demographic differences, thus raising a matter of social inequalities. “Climate change impacts are claiming lives, damaging human health and disrupting livelihoods in all parts of the world, right now. And the most vulnerable in our society are facing the greatest burden” says CMCC researcher Shouro Dasgupta, whose interests include studying the impacts of climate change on labor, food security, health, and inequality.

Addressing the health impacts of climate change requires a multifaceted approach, which includes public health policies and preparedness, and international cooperation. Research is essential to guide these interventions by identifying challenges, priorities and possible actions. Driven by the demand for more knowledge on this issue, the CMCC research line on Climate and Health has continued to grow and now offers actionable information and tools for policymakers.

The G20 Climate Risk Atlas consists of 20 country factsheets that bring together a comprehensive picture of the most updated scientific knowledge on climate, associated risks, and impacts on the economics, the environment and the societies, including health-related risks, from scientific literature.

For each of the largest economies in the world, the “Health” section of the Atlas explains in detail the risks of heat-related mortality, the diffusion of vector-borne diseases such as Dengue, Zika and Malaria, the climate change impacts on labor, and the interlinkages between climate change, pollution and premature mortality. These topics are also studied at different geographical levels – from the Global to the European or the sub-national – by CMCC scientists.

Heat-related mortality

Of all-natural disasters, extreme high temperature events are the main cause of weather-related mortality and they are also expected to be the main factor responsible for additional deaths due to climate change in the coming years. Urban areas, where the majority of the world’s population lives, are the most vulnerable to extremely high temperatures or heat waves, leaving urban populations more at risk than those that live in rural areas. Heat waves and extreme temperatures are more intense in heavily-built areas, exacerbating existing weaknesses and inequalities among urban populations.

“The population exposure is certainly linked to the physical exposure of the city district to heat. The built-up areas within the cities collect solar energy during the day and release it during the night. Therefore, the urban contexts heat up and stay warm much more than the surrounding green areas, even during the night. This happens to a more or less severe extent based on their shape and design,” says Margaretha Breil, urban planner and researcher at the CMCC.

“However, we cannot consider only the physical exposure: alongside this phenomenon, known as heat island, there are other conditions that can make a context more difficult to live in, and even more deadly.”

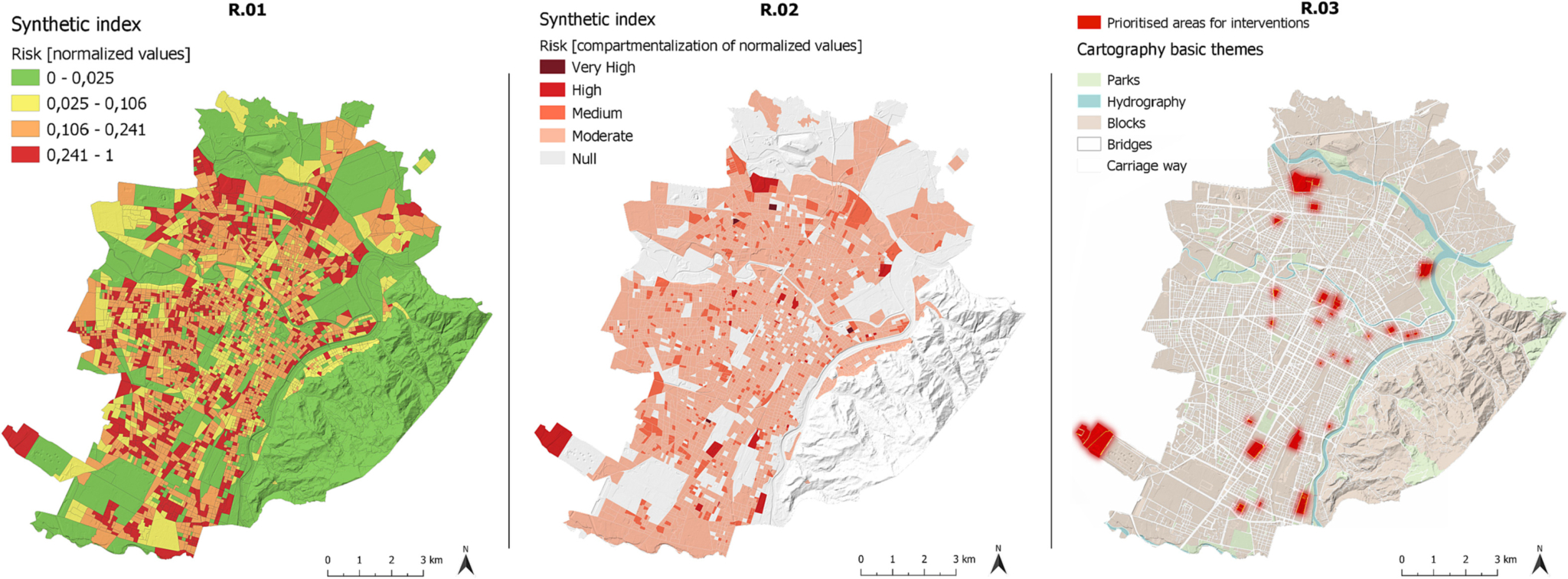

As emerged from a CMCC@Ca’Foscari study, social disadvantage can further intensify the exposure to heat risk, therefore understanding these aspects and aggregating them into heat vulnerability indices could be crucial to identifying and implementing efficient social and physical infrastructure measures – including using ad hoc spatial planning considerations and urban governance decisions.

“The need to determine the distribution of heat risk at a sub-urban level is increasingly clear: this comprehension can help to mitigate such risk by designing cities in the best possible way through all the strategies available, from the use of green areas to the choice of the building materials,” explains Paola Mercogliano, director of the Regional Models and geo-Hydrological Impacts division at the CMCC Foundation.

“Furthermore, each sub-urban area refers to hospital centers: if heat waves are combined with ongoing epidemics, the number of people that need access to these centers could increase. As the COVID-19 pandemic showed us, it is good to be prepared,” she continues.

To this end, a detailed map of Urban Heat Islands was realized as a result of a high-resolution risk assessment analysis led by CMCC on the heat-health nexus in the city of Turin (Italy) and provides insights for local policymakers in the definition of medium and long term adaptation measures to implement at the local scale.

The results of the study allowed for the identification of Urban Heat Islands in the city of Turin, and the associated risk for the population, based on their exposure and vulnerabilities, as well as the priority areas for intervention on a highly detailed scale.

Read also: The urban divide: unequal distribution of heat-related risks on city dwellers

Another recent study investigates the intersection of older adults’ health and climate change, revealing two significant trends – an aging population and increasing temperatures – portend a potentially dire future. The authors, which include CMCC’s Giacomo Falchetta, described their findings and “the factors that make older adults extremely vulnerable to deadly heat” in a longform article in the Los Angeles Times.

Diffusion of vector-borne diseases

A study by CMCC researcher Shouro Dasgupta on the relationship between climatic exposure (temperature and various measures of extreme precipitation) and malaria mortality estimates that, by the end of the 21st century, unmitigated climate change will increase all-age malaria mortality by 2.6%.

All-age malaria mortality is projected to increase in all the countries where malaria is currently present, with Sri Lanka and Philippines experiencing the highest increases. Furthermore, the research estimates that child mortality (ages 0–4) is likely to increase by up to 20%, in some areas due to climate change, by the end of the 21st century.

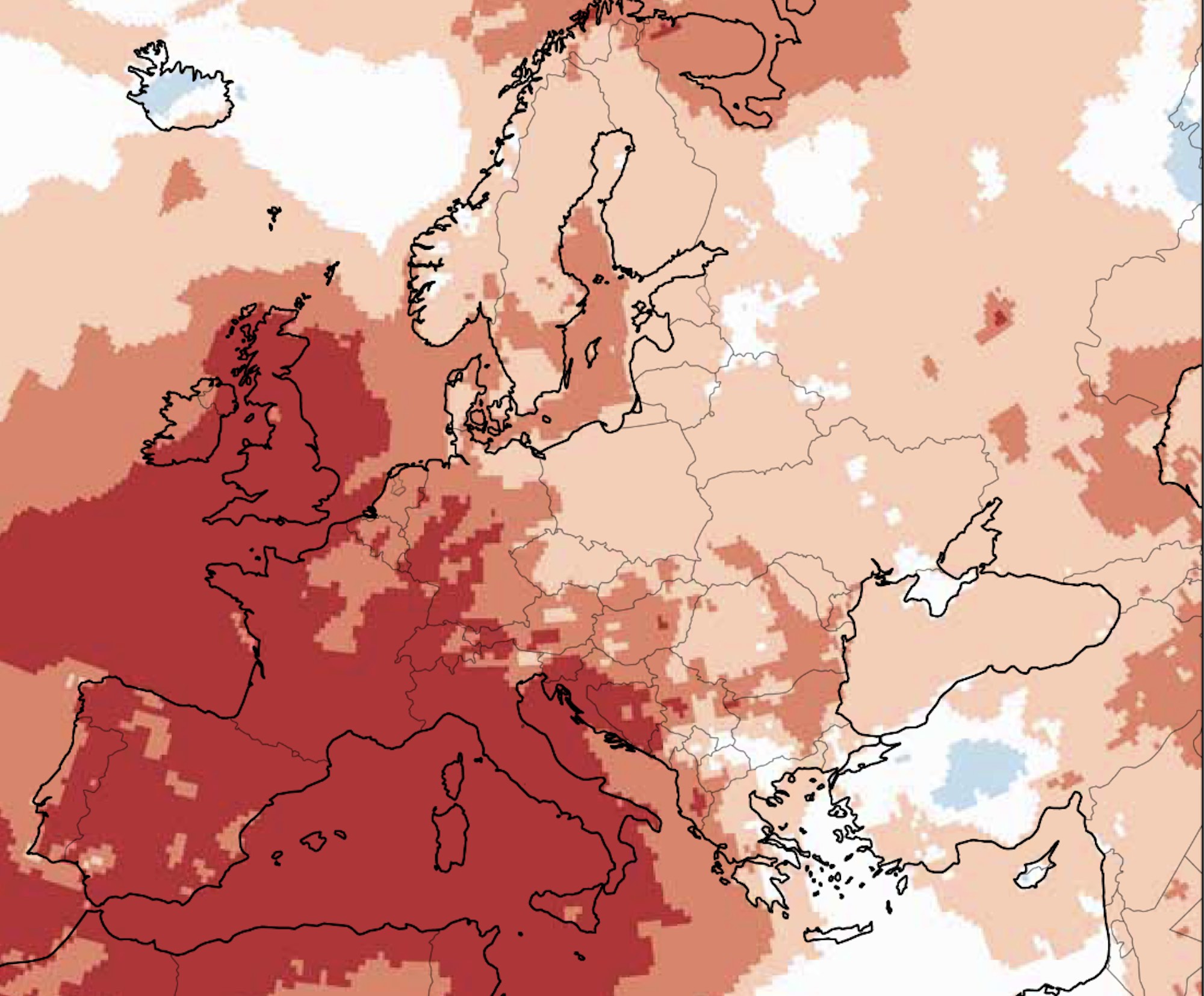

An increasingly suitable climate for the proliferation of various pathogens or their vectors may translate into higher likelihood of disease transmission also in parts of Europe, according to a report by ETC/CCA, a Consortium of European Organizations coordinated by the CMCC Foundation that assists the European Environment Agency (EEA) in supporting EU policy development on climate change impacts, vulnerability and adaptation and disaster risk prevention.

Combined with the growing number of travel-imported disease cases, this increases the likelihood of local outbreaks. In particular, Central and Eastern Europe emerge as having the highest current climatic suitability for the transmission of dengue, malaria and West Nile virus. The risk of Vibrio infections is highest around the Baltic Sea coastlines.

Tackling the emergence and transmission of zoonotic pathogens requires developing novel indicators, innovative early warning systems, efficient tools for decision-makers, and evaluating adaptation and mitigation strategies. Within the new international project “IDAlert – Infectious Disease decision-support tools and Alert systems to build climate Resilience to emerging health Threats” the CMCC will contribute to build a Europe that is more resilient to emerging health threats.

IDAlert will develop new climate and health indicators (i.e. for viruses circulating among wild birds and mosquitoes such as the West Nile Virus) and monitoring mechanisms, incorporate an inequality lens, and inform policy development across sectors, setting a new standard in support of policy and decision-making.

Climate change impacts on labor and food security

Climate change can have significant impacts on the labor force. Heat stress can affect people’s ability to work, both through the direct impacts on workers’ health and by reducing working hours and productivity. Loss of labor output also affects the economy and people’s incomes, with additional health implications.

A study co-authored by CMCC researchers sheds light on an important but understudied link between climate change and labor supply through food consumption, highlighting that increased global warming can have a significant detrimental impact on both labor supply and food security.

“Climate change has already become an issue of justice and equity” explains Dasgupta. “If we talk about impacts such as climate-induced migration and displacement, it is generally the poorest people in a country who live on the coastal lines who will be hit the most by sea-level rise. In terms of labor productivity, the greatest impacts are on sectors such as agriculture and construction, where relatively low-income workers work: they’re more vulnerable by nature of their work, and they are also more exposed to the weather events.”

Dasgupta also worked on the first edition of the Lancet Countdown in Europe, which exposes alarming increases in climate-related health hazards, vulnerabilities, exposures, and impacts across Europe. Authors demonstrated that in most of Europe heat stress due to climate change is reducing labour supply (number of working hours) in high-exposure sectors, with worrying implications for health, growth, and inequality.

In the 2022 Report of The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, Dasgupta was among those who tracked the impact of heatwaves on access to food, revealing that increasing temperatures and frequency of heat waves droughts are affecting crop yields, disrupting supply chains, and the stability of supplies.

Climate change and pollution

Air pollution is responsible for millions of deaths worldwide and crop loss every year. Both climate change and air pollution share a common origin — fuel burning — and a common solution — a clean and fair energy transition.

In a study led by RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment (EIEE) published in The Lancet Planetary Health, researchers proposed a comprehensive optimisation modeling framework, which internalizes the air pollution impacts on human mortality into the optimization of climate policies and accounts for the aerosol reductions from the air pollution policies.

The results of the study provide evidence for the need to jointly address air pollution and climate change. “Designing economically integrated policies that simultaneously generate cleaner air and less global warming increases global well-being,” explains Lara Aleluia Reis, a CMCC-EIEE researcher and one of the authors of the study. “It also facilitates the political economy of a sustainable energy transformation in key emitting regions.”