From studies investigating how future wildfire risk and activities could change under 1.5°C and 2.0°C warming scenarios, to the impacts of increased wildfire activity on human health, and even climate change itself, there is a rapidly growing body of information on the causes and consequences of wildfires.

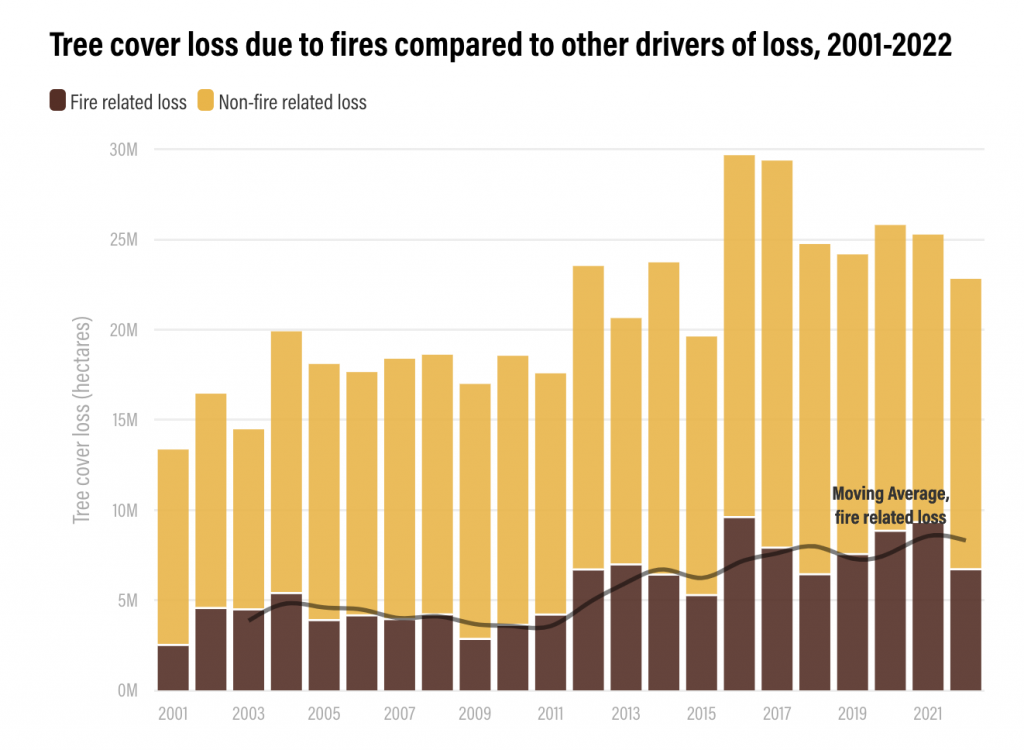

There is also overwhelming evidence that a warming climate – due to human activities – has gone hand in hand with increased frequency and intensity of wildfires, with over twice as much tree cover burnt today compared to just 20 years ago.

The impact of climate change on wildfires is mainly down to elevated temperatures leading to dry landscape and vegetation, which in turn leads to prime fire conditions. In fact, not only are wildfires more likely to occur in a warmer world, but they will also tend to burn with greater intensity and speed. Furthermore, climate change has altered precipitation patterns and contributed to other factors such as the proliferation of pests like bark beetles that kill trees and hence add to the accumulation of flammable material.

Fires occur when fire thresholds (ignitions, fuels, and drought) are crossed. When these thresholds are lowered, such as through anomalous weather for example, then the likelihood of a fire event grows.

In this context climate change is a catalyst for increased wildfire activity as it creates more favorable conditions for these thresholds to be crossed and extends the length of fire seasons and frequency of dry years.

Yet climate change is not the only factor at play. Other major causes are things like altered ignition patterns (such as human behavior) and fuel structures (including land-use changes, fire suppression, drought-induced dieback, fragmentation).

When the thresholds are crossed, the size of a fire will largely depend on the duration of the fire weather and the extent of the available area with continuous fuels in the landscape.

Furthermore, the relationship between climate change and wildfires is not unidirectional. In essence, climate change has created a “fire-climate feedback loop”, whereby a warmer climate leads to more fires, which in turn leads to more emissions and therefore further climate change. A vicious cycle.

The current state of affairs

Hardly a summer goes by – wether in the Northern or the Southern Hemisphere – without alarming stories and images of raging wildfires. But, are they actually on the rise or are we just talking about them more?

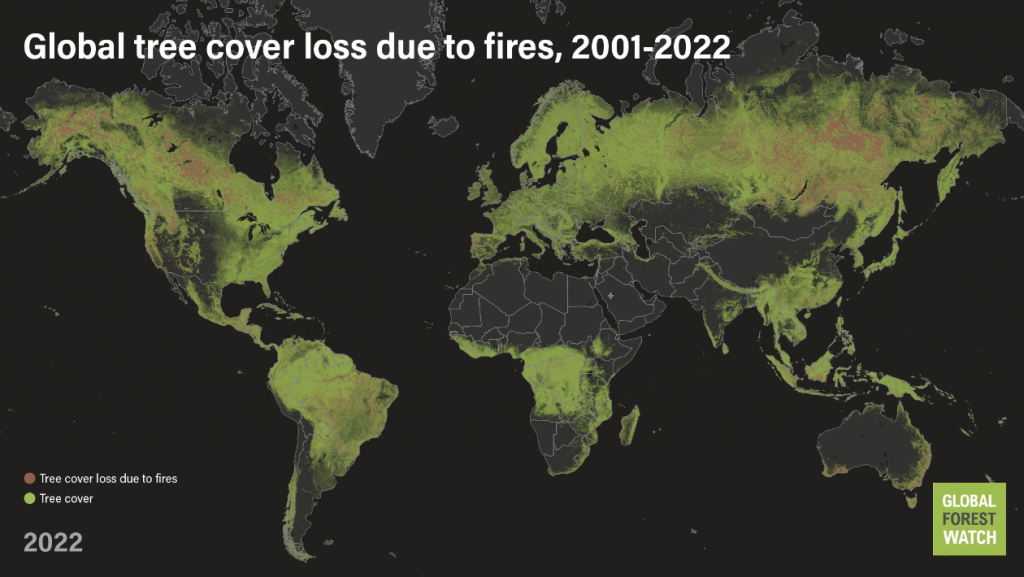

There is strong evidence to suggest that “forest fires now result in 3 million more hectares of tree cover loss per year compared to 2001 — an area roughly the size of Belgium” and that 2021 was one of the worst years for forest fires since the turn of the century, with over 9 million hectares of forest cover falling prey to wildfires — which amounted to one-third of all tree cover loss that same year.

What is even more worrying is that 2021 was not an isolated case. 2022 saw 6.6 million hectares of tree covers go up in smoke, a figure that is in line with most other years over the past decade. The current year is also shaping up to be a bad one for forest fires as they have raged across Canada, Greece and Hawaii, not to mention the onset of the Australian fire season which some experts predict could be as bad, if not worse, than the fires of 2019-2020.

Greg Mullins, one of Australia’s longest-serving fire commissioners and now a campaigner with Emergency Leaders for Climate Actions, told The Guardian that: “The wildcard in this is climate change … our fire seasons are now months longer than they used to be,” Mullins said, “I’ve been fighting fires for over 50 years now … the average temperatures are warmer, but the extremes are far more extreme.”

Climate change makes wildfires worse

According to the UNEP wildfires are becoming more intense and more frequent, ravaging communities and ecosystems in their path, with recent years seeing “record-breaking wildfire seasons across the world from Australia to the Arctic to North and South America.”

An influential 2022 report, Spreading like Wildfire: The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires, by the UNEP and GRID-Arendal, established that “climate change and land-use change are making wildfires worse,” as well as predicting that extreme fires will increase even in areas that have not seen much fire activity in the past

A 2016 study, found climate change led to an increase in dry organic matter which in turn doubled the number of large fires between 1984 and 2015 in the western United States. According to a 2021 study supported by NOAA climate change has been the main driver of the increase in fire weather in the western United States.

Drought and persistent heat were also deemed to be determining factors in the extraordinary wildfire seasons from 2020 to 2022 across many western states, a three year period which was saw fires claim well above the 1.2 million acres per year burned since 2016.

And things are likely to get worse as temperatures continue to increase. Future projections for the western US show that if temperatures rise by 1°C then the median burned area per year may increase by as much as 600% in some places.

A global problem

Just like climate change, wildfires have no borders. In the summer of 2023 alone approximately 4% of Canada’s total forest area went up in smoke in what was an unprecedented fire season which has already doubled the previous records for both burned area and carbon emissions.

Dr Yan Boulanger – a research scientist at Natural Resources Canada told Carbon Brief that – “the word ‘unprecedented’ doesn’t do justice to the severity of the wildfires in Canada this year” adding that, “from a scientific perspective, the doubling of the previous burned area record is shocking”.

The World Weather Attribution service established that hot and dry weather conditions were important drivers of these wildfires.

Extreme heat and wildfires were not just confined to the Americas. The summer of 2023 has seen record-breaking climate extremes on all continents. The first week of July was the planet’s hottest week on record, and saw countries across the Northern Hemisphere grapple with record-breaking heat.

In July 2023, wildfires in the Mediterranean saw over 135,000 hectares of land burn across southern Europe over the course of less than two weeks. Greece had a particularly alarming fire season, with the Prime Minister Mitsotakis saying that Greece would double its budget for natural disasters linked to climate change, bringing the total fund to €600 million, as well as announcing a 10% discount on the tax on property insurance and compulsory insurance for medium-sized and large businesses.

“It is time to start a public debate on the mandatory insurance of all homes and businesses,” he said at a press conference.

Heat waves and summer droughts are believed to be two of the main causes of increased fire activity in the Mediterranean region, with instances such as the 2022 record-breaking heat and drought in Spain bringing destruction to 70,000 hectares of forests due to fire.

Yet, roughly 70% of forests affected by wildfires are boreal forest regions. “Though fire is a natural part of how boreal forests function ecologically, fire-related tree cover loss in these areas increased by a rate of about 110,000 hectares (3%) per year over the last 20 years — about half the total global increase between 2001 and 2022,” reports the World Resource Institute.

Evidence indicates that the rise in wildfires in boreal regions is also due to the fact that northern high-latitude regions are warming at a faster rate than the rest of the planet, providing another indication that climate change is a key driver of forest fires.

Perhaps the most well documented example of boreal wildfires are those that swept through Russia in 2021, which was also attributed to an extended heatwave in the region that researchers claim would have been practically impossible without human-induced climate change.

Tropical forests are also susceptible to increased wildfire activity. Previous studies found that in some years, forest fires accounted for more than half of all carbon emissions in the Brazilian Amazon. This suggests that the Amazon basin may be nearing or already at a tipping point for turning into a net carbon source.

Attributing forest fires to climate change

Attribution is a process by which climate science attempts to pinpoint extreme weather to climate change. In these attribution studies, “scientists use models to compare the world as it is today to a ‘counterfactual’ world without human-caused climate change.”

However, finding the exact cause and effect relationship between climate change and wildfires, and vice versa, is not as easy as it may at first seem.

Not all wildfires have the same impact on the climate and recent research suggests that some wildfires may not even contribute to global warming, but rather lead to some cooling as water droplets that brighten clouds and smoke aerosols are released into the atmosphere, reflecting sunlight back into space and leading to localized cooling in the lower atmosphere. A process similar to that caused by some volcanic eruptions.

Although this temporary cooling effect is, in most cases, nullified as soon as rain brings the aerosols back down to earth, some wildfires, such as those that ravaged Australia during the 2019-2020 fire season, are believed to have produced widespread smoke-induced cooling that some research suggests may even have influenced the recent “triple dip” in the La Niña weather pattern.

What is certain is that wildfires impact the climate in extremely complex ways. “We need to understand the net outcomes because we need to understand how fast to reduce our human CO2 emissions,” says Matthias Stocker from the Wegener Center for Climate and Global Change at the University of Graz, Austria.

And this complex relationship is also reflected in our understanding of the way in which climate change impacts wildfires. Recent controversy, reported in The Washington Post, highlights how studies have tended to focus on the impact of climate change on the increase in wildfires and less on the impact of forest management and other human activities.

“Discussing the significance of one factor can be seen as ignoring the existence of the other,” reads the article, which highlights the need to “both acknowledge the great dangers of climate change and also recognize the multifaceted nature of any disaster.”

Being better prepared

Wildfire management and prevention continue to be key areas where we can improve. To this end, numerous tools have been developed.

One example in the Mediterranean region is the bringing together of traditional and scientific knowledge for improved fire management and coastal adaptation. On Italy’s Adriatic Coast, a close interaction between the various types of winds and fires have led to increased fire activity and the Civil Protection unit together with AdriaClim have pioneered new tools and technologies for dealing with these conditions, including the use of drones to monitor flames and precise weather forecasting to predict their trajectories.

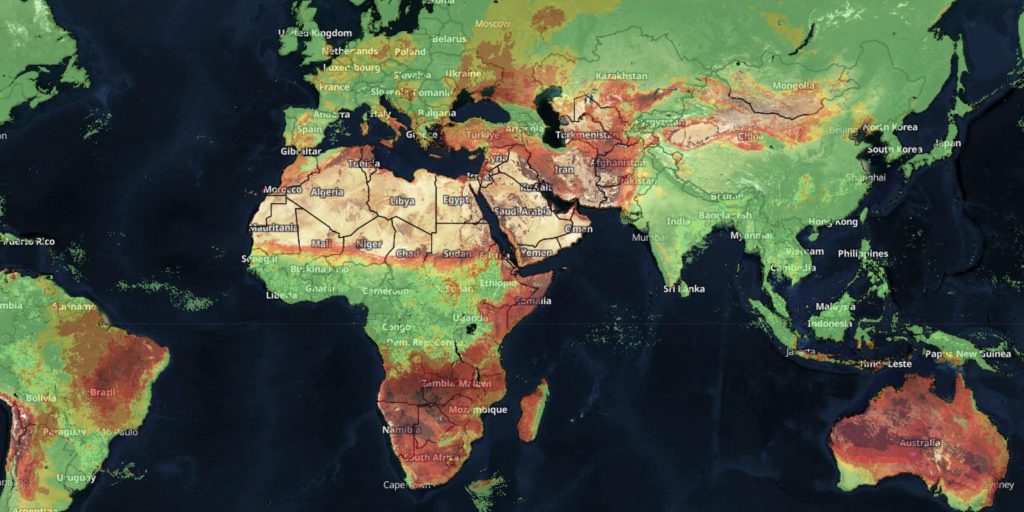

Another example is the Global Wildfire Information System (GWIS) which provides a local and global mapping tool, as well as evaluation of fire regimes and effects, with tools that enable operational wildfire management.

Their maps, such as the one shown above, can provide fire danger forecasts up to 10 days in advance, reveal lightning occurrence and active fire detections, as well as providing near-real time burnt area perimeters, and fire emissions.

Furthermore, the aforementioned UNEP report calls on governments to rethink their approach to extreme wildfires, advocating for a new ‘Fire Ready Formula’ and describing ecosystem restoration as a crucial element in fire risk prevention.