On 14 July, the European Commission announced its draft legislation – the Fit for 55 package – proposing measures for cutting the bloc’s greenhouse gas emissions by 55 per cent compared to 1990 levels. Among the measures are reforms to the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), as well as the introduction of carbon pricing at the border, via a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) that taxes high-carbon imports from countries with lower environmental standards.

The idea of implementing carbon pricing mechanisms has been brewing in the EU for quite some time. In 2019, during the build-up to her election Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, said she would “introduce a carbon border tax to avoid carbon leakage”.

Following her election in 2019 and with the introduction of the Green New Deal developing a CBAM came to be seen as a tool for both creating leverage over other countries, “should differences in levels of ambition worldwide persist”, as well as “an alternative” to existing protections against carbon leakage under the EU ETS, namely free allowances.

Therefore, the Commission proposes a mechanism to ensure that, even when they are from countries with less strict climate rules, companies importing into the EU have to pay a carbon price as well.

Fit for 55

“Policymakers recognise that to increase ambition they need to apply a carbon carrot and stick approach,” says Massimo Tavoni, director of the RFF-CMCC partnership. A carbon tax and CBAM provide the stick, while money generated from these instruments can then be used as a carrot and ensure a just transition.

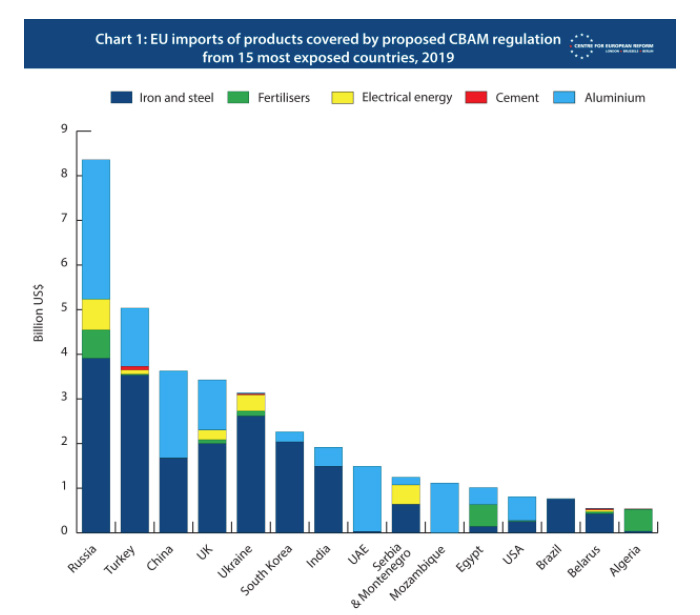

The CBAM in particular has been met with a mixed reception, with some critics seeing it as risky and protectionist strategy that could create international conflict, adversely impact lower income countries that rely on exports and possibly undermine crucial climate negotiation processes in the build-up to COP26 in Glasgow.

Understanding the complexities of carbon taxes and carbon pricing is crucial. “It is important to distinguish between the domestic carbon taxes and the CBAM as they have different roles to play. People are confusing these two approaches which has led to some misguided critiques,” explains Tavoni.

Carbon tax and carbon pricing

Set up in 2005, the EU Emissions Trading System was the world’s first international emissions trading system which went on to inspire the development of emissions trading in other countries and regions.

The current EU ETS cap-and-trade carbon market regulates airlines and industrial sites responsible for nearly half of the bloc’s overall emissions. However, to protect firms that would be at a disadvantage in global markets, the system also provides “free allowances”, including subsidies and free pollution permits, to help European firms compete with producers in places with lax environmental standards.

In the new Fit for 55 package, the EU proposes significant reforms to the EU ETS by increasing the scope of EU carbon trading to cover emissions from shipping, buildings and road transport, as well as administrative changes designed to bring the existing EU ETS in line with the more ambitious 2030 EU climate targets.

The the EU currently solves the problem of “carbon leakage”, which involves European companies responding to the carbon taxes by moving their productive activities abroad, by offering free allowances and compensation for the indirect carbon costs of higher electricity prices.

However, this approach has come under fire with critics claiming it amounts to protectionism and does not help advance climate ambition. The new solution, presented in the Fit for 55 package, is to gradually replace the free allowances with carbon pricing at the border, namely the CBAM.

Between 2025 and 2035, producers of high carbon goods such as aluminium, cement, fertilisers and steel will face gradual cuts to their subsidies. At the same time, importers of these goods will be struck with at the border pollution permit costs, thus levelling the playing field, and in the eyes of the EU, providing an added incentive for global ambition on climate change as countries will set prices on carbon at home to avoid being taxed on their exports.

The carrot and stick approach

“Why implement a CBAM? Firstly, due to an issue of competition, you don’t want your companies to move their productive processes abroad to non-regulated areas where there isn’t a price on CO2”, explains Tavoni. “However, the empirical evidence of these risks is weak. The second and most relevant reason is to boost ambition coherent with 2-degree goal set out in Paris.”

Why do we need a 'Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism'?

As we raise our climate ambition, we need to prevent business moving abroad to countries with weaker rules.

The Mechanism will ensure that companies importing into the EU have to pay a carbon price as well.#EUGreenDeal pic.twitter.com/Xz9COP8080

— European Commission 🇪🇺 (@EU_Commission) July 17, 2021

Yet critics fear that CBAM will be hard to implement, not least of which due to the intrinsic complexity of establishing exactly how to tax imports whilst ensuring compatibility with the World Trade Organization agreements.

On the other hand, if enough countries agree to apply CBAMs then they have the potential to act as a coercive measure that convinces others to step up ambition and price carbon at home – rather than losing out on revenue at the border.

“In an ideal world the CBAM would not even need to be implemented but rather would act as a credible threat so that all countries step up ambition”, claims Tavoni. “Everyone realises the complexity and potential dangers to this instrument because it can create strong international pressures and have negative effects on climate negotiations. However, at the same time it can serve as a sort of scarecrow that helps countries increase ambition.”

Leaving no one behind

“Reforming the EU ETS was necessary. However, critics believe that the measures presented may not be sufficient to protect businesses and ensure a just transition,” says Tavoni.

For example, the cost of carbon taxes and import tariffs would inevitably impact EU consumers, raising fears of a repeat of the gilet jaunes protests in France, where a carbon tax was met with widespread opposition.

“The lesson of the gilet jaunes crisis is not that carbon pricing is impossible, but that it has to be done with an awareness of the distributional effects. If you want to adjust energy prices you have to offset the higher costs with redistributive payments to those whose incomes are squeezed most severely,” says historian Adam Tooze, when speaking to Carbon Brief.

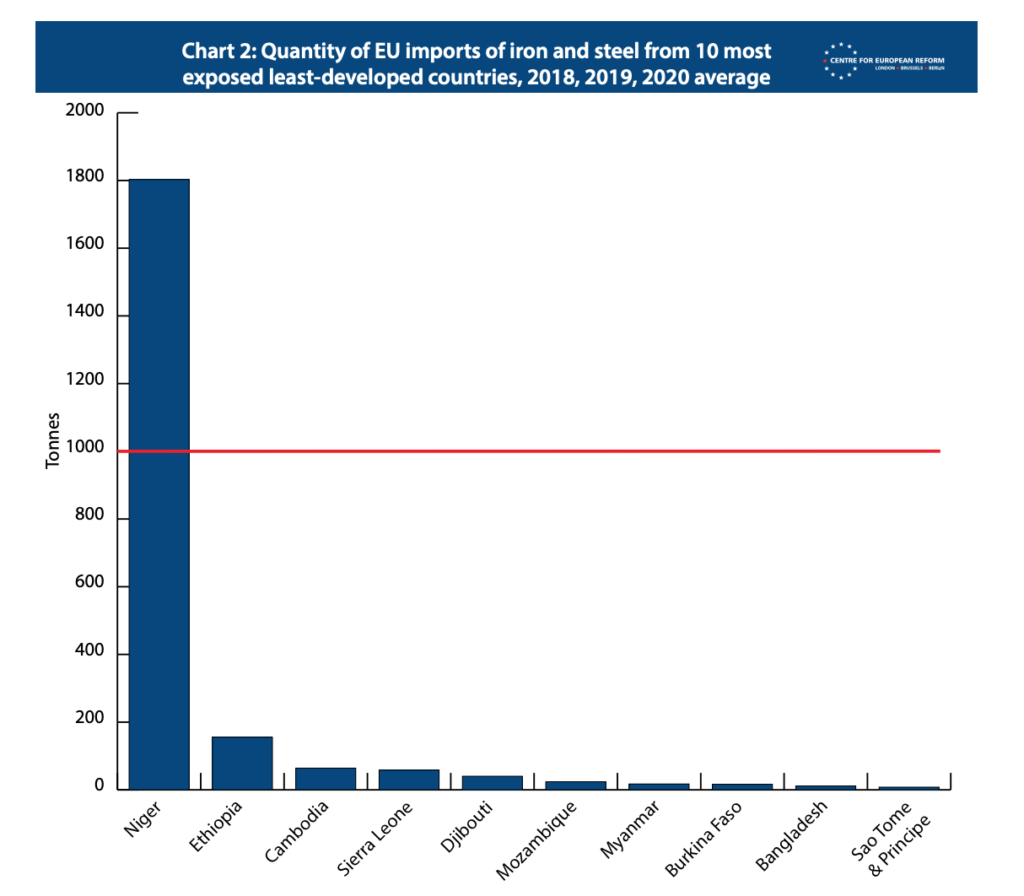

Furthermore, exporting countries are typically LEDCs so the CBAM may put an unfair burden on them. From the point of view of equity this doesn’t work and presents a series of challenges, which could be solved by redistributing the income generated from the mechanism, thus ensuring a just transition.

Equity and a just transition are therefore a fundamental aspect, and carbon pricing and carbon taxes can be leveraged to ensure that no one is left behind both domestically and internationally.

The Fit for 55 packages specifies that the estimated €2bn raised directly by the CBAM in 2030 will be allocated to the EU’s “own resources”, making it a revenue-raising tool to help the commission pay back its €750bn in pandemic recovery funds. Although this doesn’t specify where the money will be invested it leaves open the possibility of it being used to assist the transition.

Furthermore, the commission is also considering the implementation of a “social climate fund”, which commission president Ursula von der Leyen claims “embodies our commitment to a just transition” and that, “The fund can compensate vulnerable groups for higher costs of heating and transport fuels, and help invest in cleaner solutions […] It can provide temporary direct income support, help citizens finance zero-emission heating or cooling systems, or purchase a cleaner car.”

From Europe to the G20 and beyond?

In the days following the EU’s new package proposal, G20 finance ministers met at the Venice International Conference on Climate where they agreed that the “wide set of tools” to cut emissions and create a more sustainable economy should include, “if appropriate, the use of carbon pricing mechanisms and incentives, while providing targeted support for the poorest and the most vulnerable”.

Policy-makers and key international experts are gathering in Venice for the #G20 High-Level Tax Symposium to debate on how tax policy can contribute to addressing climate change and environmental challenges. #G20Italy pic.twitter.com/08wIbFOL3V

— G20 Italy (@g20org) July 9, 2021

A promising sign that the G20’s intentions are to raise ambition in the build-up to their meeting in Naples where the issue of how to meet the Paris Agreement objectives is taking centre stage.

“Countries committing to climate neutrality, such as Europe, are eager to ensure that decarbonization spreads around the world and significant climate benefits accrue,” explains Tavoni. “Border measures should be thought of as motivating enhanced ambition, not as protectionists. Currently, it is not clear this is the case.”