The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has produced its Global Assessment Report, the first since the watershed Millennium Ecosystem Assessment published in 2005. Involving three years of work and over US$2.4 million, the IPBES Global Assessment brings together over 15,000 scientific papers and government data references. Known as the ‘IPCC for Biodiversity’, IPBES is the go-to source of information for policymakers examining causes of biodiversity and ecosystem change, their effect and potential policy options for contrasting them.

On the 6th of May the Report’s key findings were launched in Paris where Government representatives from over 130 countries were present. The report concludes that around 1 million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction, most of which in the next few decades and on an unprecedented scale in human history. The numbers are staggering: average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20%, mostly since 1900; over 40% of amphibian species, around 33% of reef-forming corals and more than a third of all marine mammals are at risk.

What are the causes?

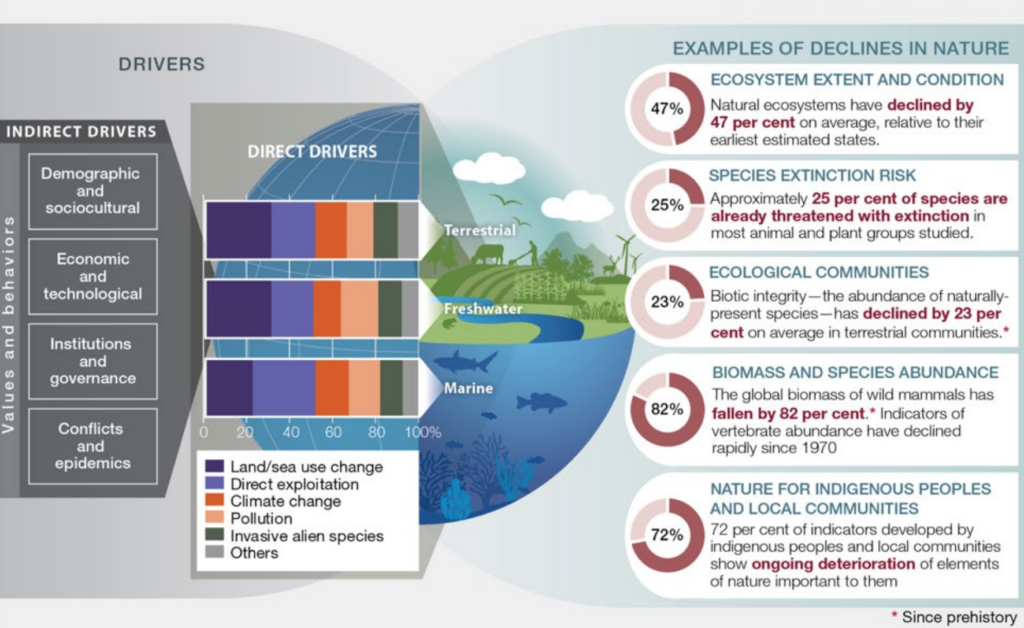

The report identifies 5 main drivers: changes in land and sea use; direct exploitation of organisms; climate change; pollution; and invasive alien species.

The first two factors are the most pervasive with three-quarters of the land-based environment and about 66% of the marine environment having been significantly altered by human actions: more than a third of the world’s land surface and nearly 75% of freshwater resources are now devoted to crop or livestock production. Alarmingly, over half of the world’s intact forest depletion has been caused by an increase in agriculture and only 3% of the world’s oceans can be considered free from human pressure.

Furthermore, although climate change, pollution and invasive species have had a comparatively low impact their role is increasing exponentially as greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, having doubled since 1980. Even if we are able to remain below the 1.5C to 2C degree mark outlined in the Paris agreement, this will still put a huge amount of strain on most species.

What can we do?

Although the report is extremely alarming it does give room for some hope and addresses potential solutions to our current predicament. First and foremost it advocates “transformative change”, in reference to “a fundamental, system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values.”

On a policy and government level this includes implementing more sustainable policies that move our current economic paradigm from one based on continuous growth to a more sustainable alternative. This could include moving away from the use of GDP as the main meter of economic wealth, implementing financial incentives for green infrastructure and removing subsidies to damaging sectors such as the fossil fuel industry.

The role of indigenous peoples in providing an alternative model to the man nature relationship is also significant. The report highlights how “regional and global scenarios do not have enough and would greatly benefit from explicit consideration of the views, perspectives and rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, their knowledge and understanding of large regions and ecosystems, and their desired future development pathways.”

However, it isn’t just about macro-level measures and policies, but also about how we can contribute as individuals, above all by being conscious of how our consumption of food and material goods impacts the planet.