In the ever-pressing battle against climate change, securing funds for climate adaptation remains a pivotal yet underserved element. As the world grapples with the consequences of a changing climate, the urgency to fund adaptive solutions has never been more evident.

Climate finance encompasses a complex landscape, marked by existing gaps in both the required funding and the ability to track them accurately, particularly in the realm of adaptation. Innovative solutions aimed at enhancing the resilience of communities to climate change exist, but investors need to allocate funds in that direction, which requires improved data and information. A better understanding of the climate adaptation finance space, and the opportunities it holds, is critical to closing these funding and information gaps.

The adaptation finance gap

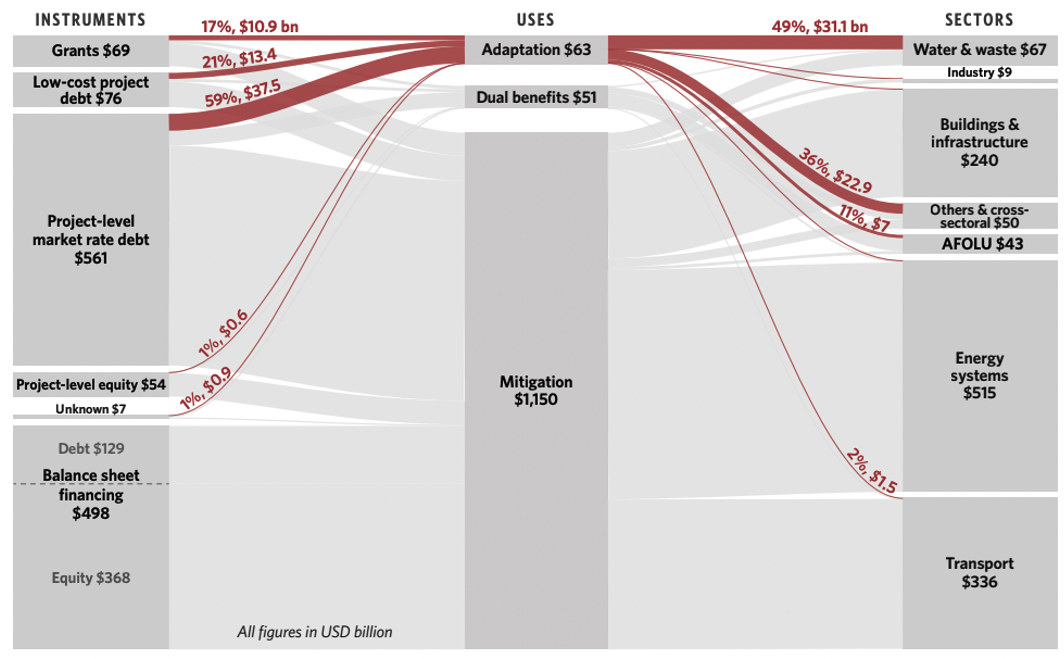

The recently released Global Landscape of Climate Finance by Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) reveals a milestone: total global climate finance surpassed a trillion dollars annually for the first time in 2021 and 2022, almost doubling over the past four years. This increase was primarily driven by new financial flows, especially in the renewable energy and transportation sectors.

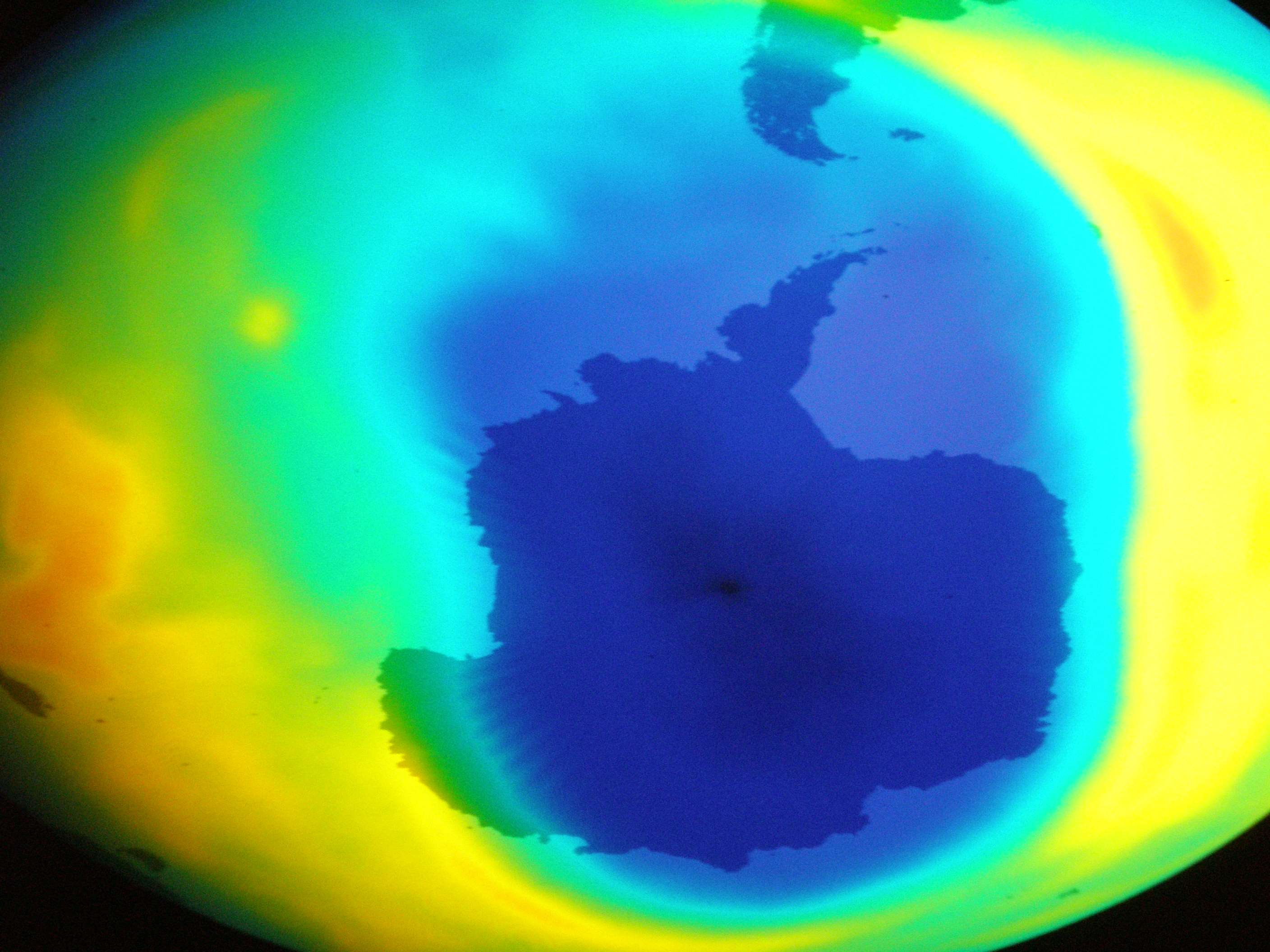

“We are heading in the right direction, but these data do not entirely constitute good news,” explains CPI Global Managing Director Barbara Buchner, emphasizing that the financing needs to meet the Paris Agreement goals by 2030 are five times higher. “Worse still, the adaptation finance gap is widening. Adaptation finance grew modestly in absolute terms, reaching USD 63 billion on average per year in 2021 and 2022, but has decreased in terms of overall share of global climate finance, dropping to only 5%.”

CPI projects that developing countries will require an estimated USD 212 billion annually in adaptation finance by 2030. The UNEP estimate is even higher: in the Adaptation Gap Report 2023, the costs of adaptation are estimated to be in a plausible central range of US$215–387 billion/year for developing countries this decade.

As for the sources of funding, mitigation funds primarily originate from the private sector, whereas adaptation finance is still funded mainly by the public sector (98%), according to the CPI report, which highlights that adaptation finance tracking challenges continue to impede the understanding of progress of both public and private flows.

Improving tracking of adaptation finance – and estimating the gap

Tracking adaptation finance and quantifying the gap to reach what’s needed remains highly challenging.

“One of our key sources of information to understand the size of the adaptation finance gap is current National Adaptation Plans, which estimate countries’ funding needs,” explains Morgan Richmond, the lead analyst for CPI’s Adaptation and Resilience workstream. “But these plans are imperfect because capacity and funding to develop them can be limited and there is uncertainty about future risks. Assessing the adaptation finance gap is also challenging because it requires a collective agreement on what ‘full’ resilience looks like. This compares to mitigation where emissions targets are relatively more easily defined.”

Private sector reluctance to explicitly label funds as ‘adaptation finance’ adds complexity. CPI is currently working on an approach that more accurately represents private sector contributions.

“Annually, we tracked about USD 1 billion in private sector adaptation finance in 2021-2022. This is genuinely low, but global climate finance tracking today also misses capital flows because the private sector largely does not label flows as ‘adaptation finance’ in the same way that the public sector does. So, we’re trying to figure out new ways to identify finance that can be included in the definition of ‘adaptation’. This will allow us to shift the narrative in a more accurate way.”

Richmond believes that identifying existing private adaptation finance could adjust the currently incomplete picture that “there is almost no finance from the private sector for adaptation” to highlight opportunities for more investment.

A Lab for innovating climate adaptation finance

Over the past decade, CPI has collaborated with private and public actors to incubate new financing structures that address climate change adaptation (and mitigation) challenges in developing countries. CPI’s Global Innovation Lab for Climate Finance (The Lab) identifies promising solutions and enables them to overcome investment barriers. Since 2019, The Lab has observed an increase in adaptation solutions, and more ideas that address both mitigation and adaptation, although these are still the minority. In 2022, the Lab launched a dedicated adaptation stream to prioritize such projects.

Carla Orrego, portfolio manager for The Lab, emphasizes two reasons behind the predominance of mitigation finance: historical market trends and adaptation projects’ longer timeline to commercial viability. “The major issue with adaptation is that it takes longer to scale and thus become commercially viable, compared to mitigation solutions, such as energy and infrastructure projects. We are trying to better highlight and support more adaptation solutions, especially those with cross-cutting mandates, using innovative structuring approaches and risk mitigation tools to make investments viable.”

Adaptation instruments incubated by The Lab include financial mechanisms for both building resilience through sustainable projects and investing in adaptation technologies.

Blockchain Climate Risk Crop Insurance is an example of an adaptation instrument focused on building resilience. The instrument’s proponents, Etherisc and ACRE Africa, have been working in Kenya since 2021 to implement this model. The digital platform utilizes blockchain technology to automate crop insurance payouts indexed to local weather, ensuring fair and timely disbursements during extreme weather events. During an extreme weather event, the policies are automatically triggered, and disbursements are made directly to the farmers, facilitating fair, transparent, and timely payouts.

“This avoids the lengthy claims process, where insurers typically check whether an event occurred or not, delaying payment and causing farmers to lose the harvest season,” explains Orrego. “Thanks to this solution, which is still in the pilot phase but has proven effective, prompt and transparent payments are facilitated, enabling farmers to purchase new seeds and prepare for the upcoming harvest season. The current challenge is to reduce the cost of insurance premiums, allowing more farmers to participate and making the model replicable. In its pilot phase, this innovative model demonstrates the potential to generate annual premiums of up to USD 10 billion at scale.

Financing adaptation through private equity funds

On the funding front, the Climate Resilience and Adaptation Finance & Technology Transfer Facility, from global sustainable private equity firm Lightsmith Group, is a pioneering private equity fund with a focus on climate resilience and adaptation. It invests in growth-stage technology companies addressing the impacts of climate change across six initial technology areas: water efficiency and smart water management, resilient food systems, agricultural analytics, geospatial intelligence, supply chain analytics, and catastrophe risk modeling and risk transfer.

To launch the fund, developed with the support of the Lab, Lightsmith brought together leading investors from around the world, which include the Green Climate Fund, established by 194 countries under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2010, which committed $46 million to become the largest investor.

“I would say that’s one of the flagship adaptation solutions in the market so far,” says Orrego. “The fund operates with two sleeves, one investing in developed markets and the other in developing economies. This structure allows for cross-subsidization at the portfolio level, mitigating some risks associated with investments in developing countries. Closing in 2021 with commitments totaling $186 million, the fund stands out for its substantial size compared to other adaptation finance solutions, offering private investors double-digit returns.”

Another success story aims to assist early-stage startups developing climate solutions in Africa as they grapple with critical gaps in funding, talent, and access to knowledge. The Catalyst Climate Resilient Fund provides pre-seed capital and tailored venture building support to bridge gaps, foster innovation, and promote groundbreaking adaptation solutions. The fund harnesses a team of technical experts who offer hands-on support to startups, enabling them to achieve product-market fit swiftly and instill climate resilience among their users.

“The total annual climate finance needed for Africa stands at USD 227 billion, with the current level at USD 30 billion. Of this, USD 11 billion is allocated to adaptation and resilience in Africa, with only 3% originating from the private sector,” said Maelis Carraro, Managing Partner of Catalyst Fund, at the COP-28 side event. “Climate mitigation and adaptation through science-technology diffusion and entrepreneurship development in Mediterranean and African regions“, co-organized by CMCC, the Union of the Mediterranean and Ca’ Foscari University of Venice.

“Catalyst Fund blends capital from concessional and commercial equity investors” explains Orrego. “It boasts an innovative financial structure, investing in early-stage ideas and providing multiple rounds of investments to the startups they support. Initially, it’s seed capital, followed by early-stage capital, and ultimately continuation of capital.” The fund backs startups such as Sand to Green, a company in Morocco transforming desert into cultivable land through agroforestry and solar-powered desalination units, and Agro Supply, which employs a USSD system in Uganda, allowing farmers to save via a QR code system on their phones. They can later use these savings to access drought-resistant seeds and other inputs, ensuring farmers have them in case of adverse weather seasons and drought.

While the finance gap for climate adaptation is large, the opportunity for private sector investment is enormous, both in emerging and developed markets. Examples like those highlighted above show innovative approaches to mobilizing private investment to close the adaptation finance gap. As private investors become more familiar with the business models, financing structures, and risk profiles for adaptation projects and technologies, we can expect to see an uptick in investment, explains CPI. The opportunity is too large and too important to ignore.