Heat at work

Extreme heat is reshaping the world of work. Today, over 2.4 billion workers are exposed to dangerous levels of heat on the job each year, with outdoor and physically demanding sectors such as agriculture and construction at the greatest risk. The consequences are far-reaching: lost working hours, rising rates of heat-related illness and death, and sharp economic losses.

In 2024 alone, extreme heat may have cost the UK over 100 million working hours. Under a 3°C warming scenario, global labour supply could shrink by up to 25 percentage points in high-exposure sectors, driving GDP losses projected at 5.9% in South Asia and 3.6% in Africa by the end of the century. In the EU alone, moderate warming could cut GDP by nearly half a percentage point by 2050.

Yet, despite the mounting evidence, many countries at the global level still lack enforceable heat protection policies for workers. “What we need is proactive labour protection policies. Policies that take local contexts into account and not one size-fits-all type policies,” says CMCC scientist Shouro Dasgupta. “It is in the economic interests of employers to provide adequate protection to workers.”

Without urgent mitigation and adaptation, extreme heat will continue to erode productivity, worsen inequalities, and threaten global food security, ultimately becoming one of the defining challenges for both labour markets and public health in the decades ahead.

Unequal access to cooling

Rising temperatures are exposing a growing divide: who can afford to stay cool, and who cannot. Global demand for air conditioning is rapidly increasing – an average of 10 new units will be sold every second for the next 30 years – yet access to cooling remains deeply unequal. While global ownership is set to rise from 28% today to as much as 55% by 2050, in Africa penetration may remain as low as 9–15%, far below the global average.

For households that do adopt AC, the costs can weigh heavily on families: low-income families spend up to 8% of their budget on electricity for cooling, compared to just 0.2–2.5% for wealthier households. This imbalance creates what CMCC researchers call “cooling poverty”, a form of energy poverty that captures both the inability to afford adequate cooling and the burden it imposes.

The consequences go far beyond comfort: without affordable and sustainable cooling, communities face heightened risks to health, food security, education, and productivity during heatwaves. As CMCC scientist Enrica De Cian notes, “the concept has many important policy implications as it points at the importance of addressing the risks related to heat exposure with effective coordination between different sectors, such as housing, healthcare, food, agriculture, and transport.”

With cooling demand projected to drive up global emissions by the equivalent of Germany’s or Indonesia’s annual footprint, investing in clean energy solutions like solar will be key to breaking the cycle of inequality, and ensuring that cooling is a right, not a privilege.

Our cities are heating up fast

Across Europe, exposure to heatwaves jumped by 57% between 2010 and 2019, compared to the previous decade. Without urgent adaptation, annual fatalities could rise from today’s 2,700 to as many as 50,000 by 2050.

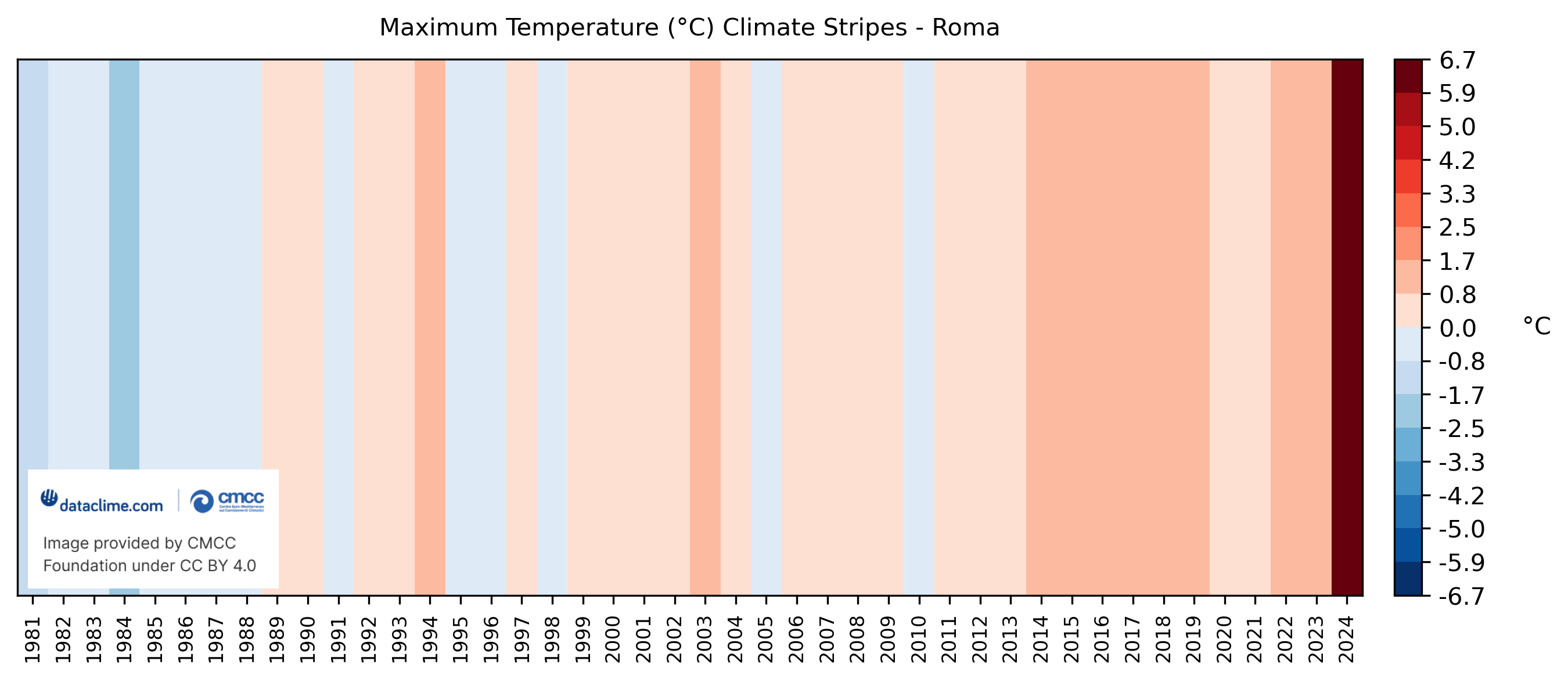

Rome offers a stark example: 2024 was its hottest year on record, with 36 tropical nights, 53 days of extreme heat stress, and a 2.5°C rise above the historical average. June 2025 marked the warmest June ever across western Europe, with “feels-like” temperatures peaking at 48°C in Portugal.

Vulnerable populations – the elderly, low-income households, and marginalized communities – are hardest hit, often living in poorly insulated homes with limited access to cooling or green spaces. With Europe’s urban population projected to reach 84% by mid-century, addressing extreme heat is essential for saving lives and protecting cities.

Urban heat islands: Risk hotspots

Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) make these trends worse, with cities warming up to 9°C above surrounding areas due to heat-absorbing materials, dense construction, and sparse vegetation. Defined as a temperature difference between urban and rural areas, UHIs disproportionately affect vulnerable groups, intensifying mortality and morbidity during heatwaves.

A study across 14 major European cities highlights clear social inequalities: lower-income and marginalized residents have far less access to cooling green spaces compared to wealthier populations. CMCC experts stress that risk depends not only on greenery but also on building design, proximity to healthcare, and availability of public cooling areas, underscoring that tackling UHIs is both a climatic and a social challenge.

Europe’s adaptation challenge

CMCC scientists reviewed National Adaptation Plans from 11 European countries, analyzing the top climate hazards – including floods, droughts, sea level rise, and shifts in temperature and rainfall – and the strategies being deployed to face them.

While countries increasingly rely on institutional coordination, early warning systems, risk mapping, and public awareness campaigns, structural interventions remain far more common than nature-based or financial solutions. Moreover, implementation is uneven: few countries have legally binding measures or regular policy review mechanisms. As climate risks accelerate, faster, coordinated action is essential to protect vulnerable groups, strengthen cities, safeguard ecosystems, and reduce health impacts.

Science in action: Urban adaptation and nature-based solutions

CMCC researchers are advancing high-resolution urban climate models tested in cities like Rome and Milan, improving the simulation of urban heat and dry islands and capturing localized temperature variations.

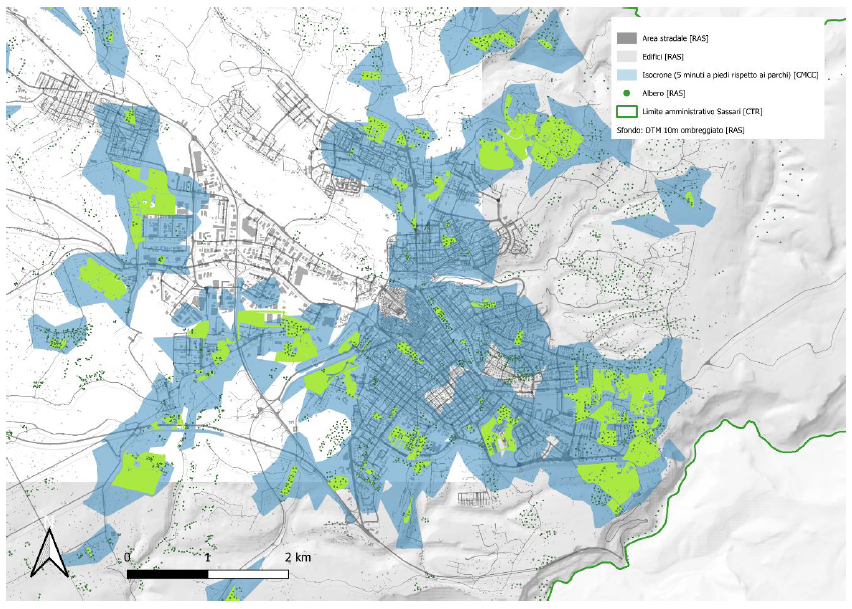

In Italy, CMCC has evaluated interventions at street level in Brescia, showing measurable drops in surface temperatures from tree planting and reflective pavements, and mapped heat vulnerability and green space accessibility in Sassari to guide local policymakers.

Tools like these are a key resource in helping cities become climate-resilient and achieve climate neutrality by 2030. The path forward lies in integrating science and policy to implement solutions that are effective, scalable, and equitable.